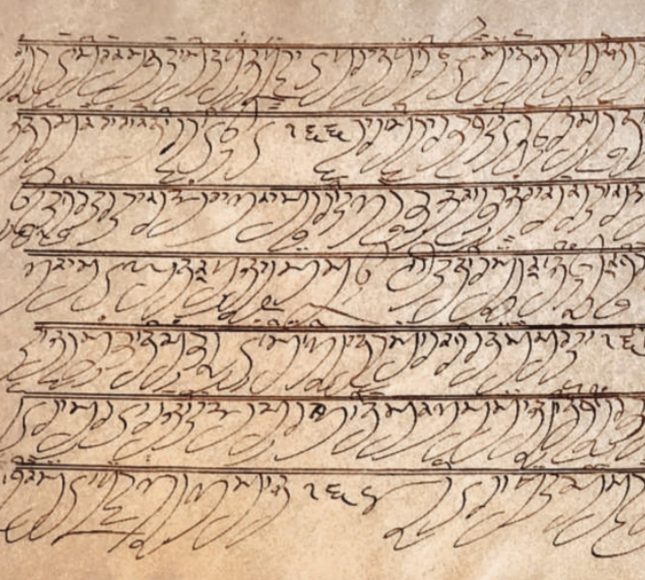

CHANDI CHARITRA, title of two compositions by Guru Gobind Singh in his Dasam Granth, the Book of the Tenth Master, describing in Braj verse the exploits of goddess Chandi or Durga. One of these compositions is known as Chandi Charitra Ukti Bilas whereas the second has no qualifying extension to its title except in the manuscript of the Dasam Granth preserved in the toshakhana at Takht Sri Harimandar Sahib at Patna, which is designated Chandi Charitra Trambi Mahatam. The former work is divided into eight cantos, the last one being incomplete, and comprises 233 couplets and quatrains, employing seven different metres, with Savaiyya and Dohara predominating. The latter, also of eight cantos, contains 262 couplets and quatrains, mostly employing Bhujangprayat and Rasaval measures.

In the former, the source of the story mentioned is Satsaf or Durga Saptasati which is a portion of Markandeyapurana, from chapters 81 to 94. There is no internal evidence to confirm the source of the story in the latter work, and although some attribute it to Devi Bhagavat Purana (skandh 5, chapters 2 to 35), a closer study of the two texts points towards one source, i.e. Markandeyapurana. Both the works were composed at Anandpur Sahib, sometime before AD 1698, the year when the Bachitra Natak was completed.The concluding lines of the last canto of Chandi Charitra Ukti Bilas as included in the Dasam Granth manuscript preserved at Patna, however, mention 1752 Bk / AD 1695 as the year of the composition of this work.

In these compositions, Chandi, the goddess of Markandeyapurana, takes on a more dynamic character. Guru Gobind Singh reoriented the old story imparting to the exploits of Chandi a contemporary relevance. The Chandi Charitra Ukti Bilas describes, in a forceful style, the battles of goddess Chandi with a number of demon leaders, such as Kaitabha, Mahikhasur (Mahisasur), Dhumra and Lochana. The valiant Chandi slays all of them and emerges victorious.

The battle scenes are portrayed with a wealth of poetic imagery. The last incomplete canto contains an invocation to God addressed as Siva. The second Chandi Charitra treats of the same events and battles, though in minuter detail and in a somewhat different mode of expression. The main point of these works, along with their more popular Punjabi counterpart Var Sri Bhagauti Ji KJ, commonly known as Chandi di Var, lies in their virile temper evoked by a succession of powerful and eloquent similes and by a dignified echoic music of the richest timbre. These poems were designed by Guru Gobind Singh to create among the people a spirit of chivalry and»dignity.

References :

1. Ashta, Dharam Pal, The Poetry of the Dasam Granth. Delhi, 1959

2. Loehlin, C.H., The Granth of Guru Gobind Singh and the Khalsa Brotherhood. Lucknow, 1971

3. Jaggi, Ratan Singh, Dasam Granth Parichaya. -Delhi, 1990

Introduction and Historical Context

The Chandi Charitar compositions are embedded within the broader corpus of the Dasam Granth, a scripture attributed to Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh Guru. These epic narratives recount the valor and exploits of the fierce divine goddess Chandi—an embodiment of strength and moral justice. Composed during a period marked by intense socio-political upheaval and oppression, these texts served both as allegorical narratives and as martial exhortations. By invoking the mythic power of Chandi, Guru Gobind Singh sought to inspire the Sikh community, encouraging them to confront and overcome the forces of evil with courage and resilience.

The tales draw upon traditional Puranic sources such as the Durga Saptasati (also known as the Chandi Path in some traditions) and the narratives found in the Markandeya Purana, reinterpreting them in the language and poetic idiom of the era. In doing so, the compositions resonate as both historical-mythological retellings and as allegories for the internal battle against tyranny, ego, and moral corruption.

Literary Form and Structural Elements

The Chandi Charitar works are typically rendered in Braj verse, employing a classical poetic style that is both vivid and rhythmic. There are two known versions of the Chandi compositions in the Dasam Granth:

Chandi Charitra Ukti Bilas:

This composition is divided into eight cantos (or sections) and comprises approximately 233 couplets and quatrains. The verses alternate between varied metrical forms—with predominant use of traditional structures such as Savaiya and Dohara—to create a dynamic and martial cadence. The language is charged with powerful imagery, using similes drawn from nature and battle to evoke the goddess’s fierce interventions against demonic forces.

Chandi Charitra (or Chandi Charitra Trambi Mahatam):

In another manuscript tradition preserved at Takht Sri Harimandar Sahib in Patna, a parallel version—also arranged in eight cantos with roughly 262 couplets—is encountered. Though similar in core narrative, subtle differences in meter (employing forms like Bhujang prayat and Rasaval measure) and imagery lend this version its distinctive lyrical texture.

Both versions interweave interpolated slokas and thematic couplets from earlier revered texts, creating an intertextual framework that reflects the inclusive, inter-religious, and mystical vision of Guru Gobind Singh.

Thematic Content and Symbolic Significance

The epic tales of Chandi are far more than mythic adventures; they are laden with allegorical significance:

Triumph over Evil:

At the heart of the narrative is the eternal struggle between the forces of good and evil. Chandi, in her many forms, vanquishes various demonic adversaries (often identified with names such as Kaitabha, Mahikhasur, Dhumra, and Lochana), symbolizing the annihilation of ignorance, arrogance, and injustice. This cosmic battle mirrors the internal war that every seeker must wage against their inner demons.

Embodiment of Divine Feminine Power:

Chandi is not only a warrior goddess in the literal sense but also an embodiment of Shakti—the dynamic and creative power of the Divine. Her fierce determination and heroic exploits inspire devotees to recognize the transformative force of divine grace, which can purge the soul of its attachments and lead to spiritual emancipation.

Metaphor for the Khalsa Spirit:

The martial ethos inherent in the Chandi Charitar texts played a significant role in shaping the identity of the Khalsa—a collective characterized by courage and a commitment to justice. The narratives served as both a spiritual metaphor and a mobilizing call for Sikhs to cultivate inner bravery and stand united against tyranny. In this way, the epic is woven into the very fabric of Sikh martial tradition.

Allegorical Reflection on Cosmic Order:

The tales also delve into metaphysical discourses on the nature of creation. Chandi is portrayed as both the destroyer of the old and the harbinger of new life—a reflection of the cyclical process of creation, preservation, and dissolution present in the universe. This duality reinforces the Sikh understanding of a living, all-pervading divine order that operates beyond human distinctions. Enduring Impact and Contemporary Relevance

The Chandi Charitar compositions continue to resonate with modern devotees for several reasons:

Inspiring Devotion and Valor:

Recited in various martial and ritual contexts, these epics serve to embolden the spirit of the faithful, reminding them that the forces of corruption and oppression can be overcome through divine grace and unwavering commitment.

Literary and Aesthetic Legacy:

The imaginative and lyrical qualities of the Chandi narratives have made them a subject of rich scholarly analysis. Their powerful use of metaphor, imagery, and classical prosody continues to influence contemporary understandings of Sikh literature and spirituality.

Allegorical Teachings for Everyday Life:

Beyond their mythological narrative, these texts offer allegories for personal transformation. Just as Chandi eradicates the darkness of the world, so too can one dispel the internal shadows of fear, ego, and falsehood by embracing the virtues extolled in these epics. Concluding Thoughts

The Epic Tales of Chandi Charitar in the Dasam Granth stand as a multifaceted testament to Guru Gobind Singh’s visionary synthesis of myth, martial energy, and spiritual wisdom. Whether read as an account of divine warfare or interpreted as an allegory for the inner battle against the imperfections of the self, these compositions remain a potent source of inspiration and an enduring reminder that true victory—both cosmic and personal—is achieved through the triumph of divine truth over all forms of evil.