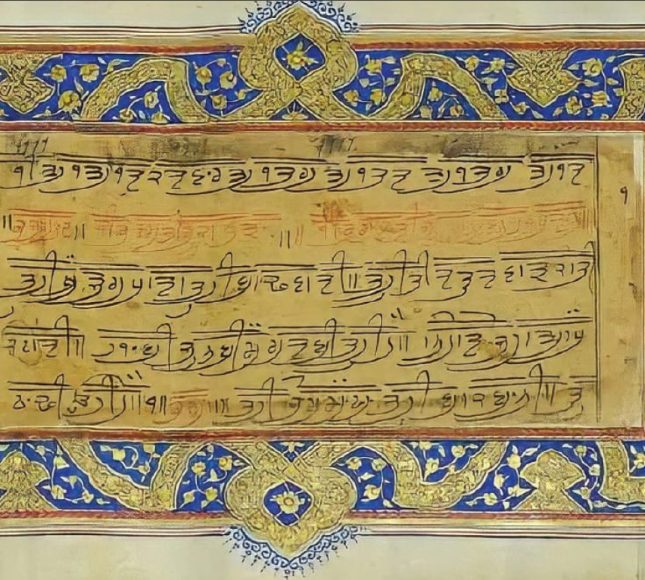

CHRITROPAKHYAN, a long composition comprising women`s tales in verse, forms over one-third of the Dasam Granth. The work is generally ascribed to Guru Gobind Singh. A school of opinion, however, exists which asserts that Chritropakhyan and some other compositions included in the Dasam Granth are not by the Guru but by poets in attendance on him. According to the date given in the last Chritra or narrative, this work was completed in 1753 Bk/AD 1696 on the bank of the River Sutlej, probably at Anandpur. The last tale in the series is numbered 405, but number 325 is somehow missing.

The tales centre upon the theme of women`s deceits and wiles, though there are some which describe the heroic and virtuous deeds of both men and women. Tale one is a long introductory composition. It opens with an invocation to weapons, or to the God of weapons; then a number of Hindu mythical characters appear, and a terrific battle between the demons and the gods follows. Finally Chandi appears, riding on her tiger, and her enemies “fade away as stars before the rising sun.” With a final prayer for help and forgiveness the introductory tale ends.

In the last Tale 405 again the demons and gods battle.When Chandi is hard pressed, the Timeless One finishes off the demons by sending down diseases upon them. Tale two tells how the wise adviser to Raja Chitra Singh related these tales of the wiles of women in order to save his handsome son Hanuvant from the false accusations of one of the younger ranis. Some of these tales were taken from old Hindu books such as the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Puranas, the Hitopadesa, the Panchatantra, from Mughal family stories, from folktales of Rajputana and the Punjab, and even from ancient Hebrew lore.

The moral they aim at is that one should not become entangled in the intrigues of wily women by becoming a slave to lust, for trusting them is dangerous. This does not mean that it is wrong to trust one`s own wife, or worthy women ; but that it is fatal to lose this world and the next by becoming enamoured of strange women and entrapped in their wiles. The theme of most of the tales, however, is that many women will stop at nothing slander, arson, murder to obtain their heart`s desire; that men are helpless in their clutches; and that if men spurn them they have to reckon with the vilest and deadliest of enemies; but that, conversely, worthy women are the staunchest of allies, and think nothing of sacrificing their lives for their beloved.In the Dasam Granth a title is given at the end of each tale.

Thirty-two of a total of 404 Tales are thus labelled “Tales of Intrigue.” The remaining 372 Tales are labelled as “The Wiles of Women.” However, while most of these are about lustful, deceitful women, there are some 74 tales of the bravery and intelligence of women, such as Talc 102 where Ram Kaikeyi drives Raja Dasaratha into battle when his charioteer is killed; or Tale 137 where Draupadi rescues the unconscious Arjun and puts his enemies to flight. Men come in for at least a small share of being deceivers. In this mixture of tales of various sorts, there are ten “moral stories” of the folly of gambling, drinking, and opiumeating.

There are also folktales; love stories of Krsna and Radha; of Krsna and Rukmini; of Aurarigzib`s sister (Tale 278); and of Joseph and Zulaikha, based on the Biblical story of Joseph and Potiphar`s wife in Genesis. The closing verses of Tale 405 have some lofty teaching about the Timeless Creator, His understanding love, and end with a plea for His continuing protection. Verses of gratitude for help in completing the composition form the final prayer of the author and close this strange mixture of the tales of intrigue, of women mostly, some worthy, many sinful, in which men are often pictured as the gullible tools of these enchantresses.

References :

1. Ashta, Dharam Pal, The Poetry of the Dasam Granth. Delhi, 1959

2. Loehlin, C.H., The Granth of Guru Gobind Singh and the Khalsa Brotherhood. Lucknow, 1971

3. Jaggi, Ratan Singh, Dasam Granth Parichaya. Delhi, 1990

Chritropakhyan: Women’s Tales in the Dasam Granth—a collection of narratives that comprise a significant but controversial portion of the text. These tales, traditionally ascribed to Guru Gobind Singh’s time, weave together themes of morality, seduction, caution, and—occasionally—valor. They offer a complex tapestry of how feminine wiles, deceit, and occasionally, fortitude have been portrayed within the cultural and literary context of the period.

Historical and Literary Context

- Canonical Placement and Dating:

Chritropakhyan (also rendered as Charitropakhyan) forms over one third of the Dasam Granth. According to traditional accounts, the work was completed on the banks of the Sutlej (possibly at Anandpur) around 1696 AD (1753 Bikram), during turbulent times when both external conflicts and internal ethical challenges were prominent. This dating situates the text amid a period of intense social and political transformation. - Authorship and Attribution:

Although the work is widely attributed to Guru Gobind Singh, debates persist among scholars regarding its authorship. Some suggest that parts of it might have been composed by poets from the Guru’s court. Regardless of its origin, the text was incorporated into the Dasam Granth—and it reflects not only a rich literary tradition but also the prevailing socio-cultural attitudes of its time. - Purpose and Use:

The primary stated aim of Chritropakhyan is didactic. The tales are intended to serve as cautionary narratives for men—warning them against the pitfalls of being seduced or entrapped by the deceitful wiles of women. At the same time, interspersed among narratives of treachery are accounts that laud the heroic or virtuous acts of certain women, offering a layered perspective on gender and morality in a rapidly changing society.

Literary Form and Structure

- Narrative Composition:

Chritropakhyan is composed in verse and spans 404 (or, in some accounts, 405) distinct chapters or “tales.” Each chapter is a compact narrative that blends descriptive imagery, dialogue, and moral commentary. Many of the tales are set within familiar mythological or courtly frameworks, drawing upon traditional Indian literary motifs. - Language and Style:

The composition employs the classical idioms of the time, using a mix of vernacular Punjabi interlaced with refined literary and even Sanskritized expressions. The vivid and sometimes provocative language is designed to evoke strong imagery, whether it is a description of a woman’s enchanting beauty or of the ruinous consequences of falling prey to her charms. - Structural Labels:

Notably, the text itself differentiates between types of narratives. Out of the 404 tales, 32 are labeled as “Tales of Intrigue,” whereas the remaining 372 are dubbed “The Wiles of Women.” This editorial distinction underscores the central thematic concern of the work and sets up its dual function—both as an exposé of sexual deception and as a moral compass warning against the perils of unbridled desire.

Thematic Content and Symbolic Layers

- Motif of Deceit and Warning:

A dominant theme in Chritropakhyan is the caution against becoming entangled in the intrigues of women perceived as deceitful. The narratives often depict women employing slander, seduction, arson, or even murder to secure their desires; the moral intent is clear: succumbing to lust or ill-advised relationships can lead to both worldly ruin and spiritual distraction. - Allegory of Inner Conflict:

Beneath the literal interpretations, many scholars argue that these tales operate as allegories for the internal battle between passion and self-restraint. The seductive wiles and treacheries represent the myriad temptations and illusions (moh) that challenge one’s path toward spiritual realization. In this light, the text functions as a metaphorical mirror for the internal duality faced by every seeker. - Dual Depictions—Virtue and Vice:

While many tales emphasize the dangers of unguarded desire, a subset of narratives (approximately 74 out of the total) extol the virtues and heroic deeds of women. Examples include accounts where women display intelligence, courage, or sacrificial love—illustrating that the portrayal of femininity in the Dasam Granth is not uniformly negative but is characterized by a tension between vice and virtue. - Social and Moral Commentary:

The overall tenor of Chritropakhyan is didactic. It offers moral prescriptions by delineating the consequences of entrapping oneself in the web of lust and deception. For many contemporaries and later readers, the text served as a cautionary guide, advising men to trust only their wives or truly virtuous women, and underscoring the destructive potential of succumbing to extramarital indulgence.

Controversies and Interpretations

- Patriarchal Lens vs. Complex Gender Dynamics:

Modern readers often grapple with the seemingly misogynistic tone of many tales, where women are predominantly portrayed as schemers. Some contemporary scholars, however, caution against a simplistic reading. They highlight that Chritropakhyan reflects the complex gender dynamics of its time—a period when courtly intrigue, honor, and social control were inseparable from literary expression. - Moral Didacticism:

Despite its controversial content, many of the tales are intended as moral lessons rather than literal historical accounts. They illustrate the dire consequences of unchecked desire and serve to reinforce a disciplined, values-oriented life. In this sense, even the more provocative narratives function within a broader ethical framework. - Literary Critique vs. Devotional Use:

In Sikh devotional practice, portions of the Dasam Granth are recited for their poetic and historical value rather than as direct prescriptions for personal behavior. Consequently, while Chritropakhyan remains one of the most debated parts of the text, its inclusion in the larger corpus also contextualizes its themes within the comprehensive, multifaceted vision of the Dasam Granth.

Concluding Thoughts

Chritropakhyan: Women’s Tales in the Dasam Granth is a multifaceted and complex work that defies singular interpretation. On one level, it is a series of vivid narratives—rich in eroticism, caution, and dark humor—that warn of the perils of succumbing to enticing but deceptive forces. On another level, it operates as an allegorical commentary on the inner struggles of desire and discipline, the nature of moral decay, and the possibility of redemption. Whether read as an unyielding patriarchal warning or as a more nuanced reflection of the socio-cultural milieu, the text endures as a provocative element of Sikh literary heritage, inviting ongoing debate and interpretation.