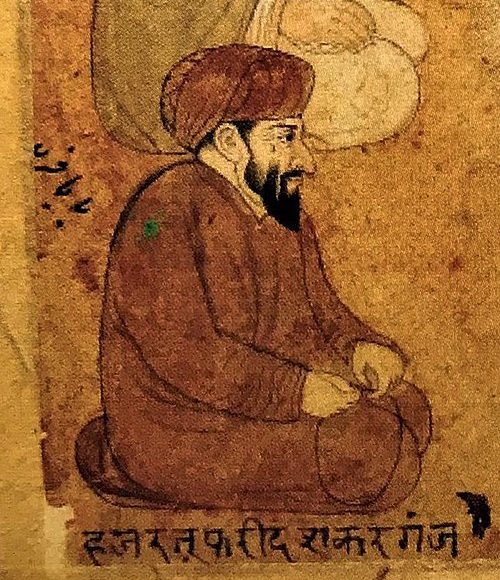

FARID, SHAIKH (569-664 AH/AD 1173-1265), Sufi mystic and teacher, who is also known to be the first recorded poet in the Punjabi language. His father Shaikh Jamaluddin Sulaiman whose family related, according to current tradition, to the rulers of Kabul by ties of blood, left his home in Central Asia during the period of Mongol incursions in the course of the twelfth century. Seeking safety and some place to settle in, he came into the Punjab where already under Ghaznavid rule several Muslim religious centres had developed and sizeable Muslim populations had grown, particularly in the areas now included in West Punjab (Pakistan). To Shaikh Jamaluddin Sulaiman was born in 569 AH/AD 1173 in the month of Ramadan a son, the future Shaikh Farid.

The newly born child is said to have been named after the Sufi poet Fariduddin Attar, author of several works on Sufi philosophy.The child became famous by the first part of his name Farid, which is Arabic for \’Unique\’. He also acquired the appellation of Shakarganj or Ganj-i-Shakar (Treasury of Sugar) or Pir-i-Shakarbar. The place of his birth, close to Multan, was called Kotheval. His father having died while he was still a child, his mother Qarsum Bibi, an extremely pious lady, brought him up. He grew up to be a great saint, combining with holiness learning in all the sciences comprehended at that time under Islamic religious studies, such as canon law, jurisprudence and mystical philosophy.

About the appellation of Shakarganj popularly given him, it is related that in order to induce the child to say his prayers regularly, his mother used to place under his prayermat a small packet of shakaror country sugar which the child would get as a reward. Once, it is said, she forgot to provide the incentive. Such was the piety of the child and such the divine favour that a packet of shakar nevertheless appeared in the usual place.On discovery, this was attributed to a miracle, and hence the appellation Shakarganj. Another explanation given is that while undergoing in his youth extremely hard penance, he in a fainting state once looked around for something to break a three days continuous fast.

Not finding anything to assuage his hunger, he thrust a few stone pebbles into his mouth. By divine intervention, the stones turned into lumps of sugar. But this name may in reality be traccable to the blessing which he is recorded to have received from his spiritual preceptor, Khwaja Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, who praised the sweetness of his disposition and of his word, and remarked; “Thou shall be sweet like sugar.” Shaikh Farid is one of the founding fathers of the famous Chishti Sufi order in India, which began its long course in the country towards the close of the twelfth century with the coming of the great saint Khwaja Mu\’inuddin Chishti. Khwaja Mu\’inuddin came to India during the reign of Rai Pithora or Prithvi raj Chauhan, the last Rajput king of Delhi, whose kingdom stretched to Ajmer and beyond.

Shaikh Farid became the disciple of Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, himself a disciple of Khwaja Mu\’inuddin Chishti. He first met his future master at Multan and became deeply devoted to him. When the Khwaja was leaving Multan to resume his onward journey to Delhi, he adjured him to follow him to the city after completing his studies at Multan, and continued his Sufi practices under the guidance of the master he had adopted. This involved, in accordance with the tradition of the Chishti order, rigorous penance and constant prayer, to subdue the flesh and acquire spiritual illumination. Included in this discipline was chilla-i-makus, constant prayer with head hung downwards for forty days.

Shaikh Farid set up a centre of devotion at Hansi, in present day Haryana, later shifting to Ajodhan, now Pak Rattan in Sahiwal district of Punjab (Pakistan). This was then a wild and arid area, with few of the comforts of life, and here he came in obedience to Khwaja Qutubuddin’s command: “Go thou and set up settlement in some wasteland.” Ajodhan is close to the River Sutlej on its western side, on the banks of one of its tributary streams. The stream was served by a ferry called Rattan. Later, in honour of Shaikh Farid it came to be known as Pak Rattan (holy ferry). The place, now a fairly well developed town, is till tills day called by that name.

It is recorded that Shaikh Farid spent his entire life from his twenty fourth year on at Ajodhan, where he made a reputation for himself by his pious and austere living and his many beneficent works. As related by his disciple, the famous Shaikh Nizamuddin Awllya, who visited him at least three times at Ajodhan, there was more often than not very little in his home to eat and the family and disciples would feel blessed if they could make a meal on dela, a wild sour tasting berry growing on a leafless thorny bush. He maintained in the tradition of the Chishti saints, a khanaqah or hospice for itinerant Sufis and others, along with a prayer house where strangers would be provided food and shelter and spiritual instruction. Here Shaikh Farid also received visits from travelling scholars, other Sufis and dervishes and from large crowds seeking his blessing.

Some miraculous stories are related of him which illustrate the great faith he inspired and the veneration in which the people held him. That the Sufis brought the healing touch to the strife torn religious scene in those times is evidenced by an incident which bears a deep symbolic character. Once someone brought a pair of scissors. Shaikh Farid put it by and asked instead for a needle, saying: “I am come to join not to sever.” Shaikh Farid, whose influence spread far and wide, had, according to a report, twenty khalifas or senior missionary disciples to preach his message in different parts of the country.

Out of these, three were considered to be the principal ones.At the head was the famous Shaikh Nizamuddin Awliya of Delhi, followed by Shaikh Jamaluddin of Hansi and Shaikh \’Alauddin\’ All Ahmad Sabir of Kaliyar, in Rajasthan.The modern town of Faridkot, which is situated close to Bathinda and would in Shaikh Farid\’s time be on the road leading out from Delhi and Hansi towards Multan, is traditionally associated with his name. Ajodhan would be distant about a hundred miles from this place. A credible story connects the name of this place, Faridkot (Fort of Farid), with the forced labour that this saint had to undergo there in the time of the local chief named Mokal, then building his fort.

By a miracle Shaikh Farid\’s saint hood was revealed and, on the inhabitants showing him reverence, he blessed the place.The Guru Granth Sahib contains the spiritual and devotional compositions of certain saints besides the Gurus. Prominent among these are Kabir, Ravidas, Namdev and Farid. The poetry of Shaikh Farid, as preserved in the Guru Granth Sahib is deeply sensitive to the feeling of pity, the subtle attractiveness of sin, inevitable death and the waste of human life owing to man\’s indifference to God and goodness. His language is of an extraordinary power and sensitivity.

The tragic waste of man\’s brief span of life in frivolous pursuits moves him to lender expression of pity and reproach. Withal he is deeply human and man\’s situation moves him to deep compassion such as would be in a man with eyes who saw a blind man standing on the edge of a precipice, about to take the fatal step into nothingness.The voice of human suffering finds in him an expression heard seldom and only in the greatest poetry.His language is the authentic idiom of the countryside of southwestern Punjab, where he spent the major portion of his life.

Yet by a miracle of poetic creation this language has become in his hands full of subtle appeal,

evoking tender emotions and stimulating the imagination. The main theme of Shaikh Farid\’s banis what in the Indian critical terminology would be called vairagya, that is dispassion towards the world and its false attractions. In Sufi terminology this is called tauba or turning away. The bani of Farid in the Guru Granth Sahib is slender in volume, but as poetry of spiritual experience it is creation of the highest order. It consists of four sabdas (hymns) and 112 slokas (couplets).

Guru Nanak, Guru Amar Das and Guru Arjan have continued the theme of some of Farid\’s couplets. These continuations appear in the body of Farid\’s bani. Guru Nanak has left a sabda in measure Suhi as a corrective to Farid\’s beautiful lyric in the same measure, which, however, appeared to view the future of the human soul in a rather pessimistic light.Certain recent writers, led by M.A. Macauliffe, have raised doubts as to Shaikh Farid Shakarganj\’s authorship of the bani, mainly on the score of its language which they think is too modern for his day. While in the course of oral transmission it may have at places taken on the colouring of subsequent periods, it is the authentic idiom of Multan Punjabi which that dialect retains to this day.

The language argument against Farid\’s authorship cannot be sustained. The Gurus would not have given this bani the place of honour they did, were they not convinced that it was composed by Shaikh Farid Shakarganj, the most revered Muslim Sufi of the Punjab. The high level of poetry, the sheer genius which has created it would make lie claim of a lesser man than Shaikh Farid to authorship insupportable. History does not know of any other man as famous as Farid, the name used in the verses included in the Guru Granth Sahib.

References :

1. Sabadarth Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Amritsar, 1964

2. Gurdit Singh Giani, Itihas Sri Guru Granth Sahib. (Bhagat Bani Bhag). Chandigarh, 1990

3. Sahib Singh, Bhagat Bani Satik. Amritsar, 1959-60

4. Vir Singh, Bhai, Shabad-Shalok Sheikh Farid Sahib. Amritsar, 1909

5. Maculiffe, M.A., The. Sikh Religion. Oxford, 1909

6. Kohli, Surindar Singh, A Critical Study of Adi Granth. Delhi, 1951

FOR about three centuries after his death, Baba Farid’s verses had been alive in Punjab, with the mureed and the mystic passing on his message, from generation to generation. Then came Adi Granth, the first official Sikh scripture, which expanded and came to be known as Guru Granth Sahib. Guru Arjan included in it the writings of Sheikh Farid, preserving his message for the times to come. This year marks the 850th birth anniversary of the Sufi mystic and scholars are still trying to reimagine his times, understand his text, translate his verses and apply his lessons to our cacophonic times.

Gurdwara Tilla Baba Farid in Faridkot. Tribune photo

Baba Farid, also known as Fariduddin Ganjshakar, was born at Multan in 1173 and died at Pakpattan in 1266. These were times of utter despair. Devastating invasions were leaving Punjab bleeding and its people in a wretched state. Farid’s verses were the balm the region needed and what’s more, he spoke in their language, their idiom.

Farid, my dry body hath become a skeleton,

Ravens peck at the hollows of my hands and feet

Up to the present, God hath not come to mine aid

Behold His servant’s misfortune

O, ravens, you have searched my skeleton and eaten all my flesh.

But touch not these two eyes, as I hope to behold my beloved

Translation by Max Arthur Macauliffe

My bread is made of wood, my hunger is my sauce

Those who eat rich meals shall come to grief

Says Farid, you must fathom the ocean which contains what you want

Why do you soil your hand searching the petty ponds;

Says Farid, the Creator is in the creation and the creation in the Creator

Whom shall we blame when He is everywhere?

Translation by Sant Singh Sekhon

Almost all forms of poetry, especially Sufi poetry, have an inherent flow and singabilty. These qualities play a pivotal role in strengthening our centuries-old vocal tradition. This is the reason why not only Baba Farid but all Sufi saints continue to shape our lives. ‘Naadaan Parinde’ in the movie ‘Rockstar’ encapsulated Baba Farid’s ideas (and a part of his verse ‘Kaaga re’), wherein the foundationfor the bridge connecting the film character’s soul to the Almighty is laid. Irshad Kamil | Lyricist

Literary critic Tejwant Singh Gill says that being a frontier region, Punjab would bear the brunt of foreign invasions. “Geographically, it was almost a desert and there was utter poverty. He brought a sense of sobriety and serenity to the life of the people harassed by invaders. He coaxed them to keep aloof from the disastrous influence of those various factors. He didn’t preach a sense of revolt, but a sense of contentment. He asked them to not be carried away into rejection. He gave moral strength to people,” says Gill, who feels Farid’s spiritualism led him to disillusionment with his ancestors, invaders themselves.

It is this calming effect on Punjab that poet Waris Shah paid tribute to in his seminal work ‘Heer’, written in 1766:

Shakarganj ne aan mukaam kita / Dukh darad Punjab da dur hai ji

(Shakarganj’s grace dispels all Punjab’s sorrows; and makes her peaceful ever more)

Waris Shah eulogised the mystic, writing that Farid’s advent to Punjab proved a boon for the land and its people. The beauty of his message was contained in delicate poetry and in a dialect similar to present-day Punjabi, earning him the sobriquet of the ‘father of Punjabi poetry’.

Not much is known about the literary traditions of the time. What is known, says historian Prof Indu Banga, is that Sufism — which fully emerged in the 8th century — had come to India by this time. “We know of a work written in Persian at Lahore in the 11th century, ‘Kashf al-Mahjub’, by the Persian scholar Ali al-Hujwiri. It talks about a dozen chains or silsilas and leading Sufis and their schools.”

These silsilas owe themselves to Ghaznavids, who had established their rule over Punjab, making it the first region in India where Sufism found its roots, she points out. “Ali al-Hujwiri came from outside but decided to settle in Lahore and write about Sufism.”

Prof Banga says people were turning to Islam by now and responding to Sufi ideas. But, so far, these Sufi mystics had been coming from outside. What set Farid, one of the founding fathers of the popular Chishti Sufi order in India, apart was that he was using the local idiom. “This means he had internalised the Sufi ideas to the extent that he could present them clearly in people’s language, his metaphors being largely related to the life around. Prof JS Grewal called it indigenisation of Sufism,” says Prof Banga.

In ‘A History of Punjabi Literature’, litterateurs Sant Singh Sekhon and Kartar Singh Duggal note: “His (Farid’s) available compositions, though written in a dialect, amply suggest a learned mind behind the sensitive idiom, a mind that has steeped itself deep in the tradition of his age and creed and is capable of absorbing the influences of his environment.”

Despair, separation and death are a potent presence in his writings. Critiquing his writings, Sekhon and Duggal say that Farid laid stress on the love of man as a means of attaining the love of God. The world appeared to him an obstacle in the way of union with God. Death is illustrated as a bridegroom and impermanence of life on this earth by the figure of a bird coming to play on the bank of a pool.

Sekhon and Duggal say that his writing never smacks of superiority. He comes down to the level of the poorest of the poor and calls himself a sinner. This endeared him to the people and this endearment, they insist, might have been responsible for his inclusion in the Sikh scripture.

Fine and poetic at the same time, his verses marked a great departure from the prevalent times and led to the foundation of Punjabi language, says Prof Gill. “Earlier dialects didn’t have much importance of their own except for conversational importance as Persian was the medium of official work. He created a poetic language,” he adds.

“Baba Farid is to Punjabi language what Chaucer is to English,” says musician Rabbi Shergill, whose oeuvre includes the composition of Farid’s ‘Birha tu Sultan’, among the mystic’s several other verses, most of which Rabbi knows by heart. “He was the foundation. He sets the tone for both Punjabi spiritual literature and also Punjabi language. Everything springs forth from these verses. He is pretty much the fountainhead of everything Punjab.”

For several centuries after his death, his successors spread his writings. One of them was Sheikh Ibrahim, whom Guru Nanak met in the 16th century. Guru Nanak recorded Farid’s poetry and his four hymns and 130 couplets were later recorded in Guru Granth Sahib.

Prof Gill says the beauty of the inclusion in the holy Granth lies in the fact that wherever the Gurus differed with Farid in terms of doctrine, they put their own couplets alongside. “The idea was not to controvert Farid but to qualify. If it were not for Gurbani, his hymns could have been lost. Guru Nanak also saved the content of the idiom from adulteration.”

Eight centuries after his death, Baba Farid remains a giant and his Faridi langar is a tradition well adopted by Sikhism. Yogesh Snehi, author of ‘Spatialising Popular Sufi Shrines in Punjab: Dreams, Memories, Territoriality’, says Baba Farid acquires a prominent position because of his attitude towards non-Muslims. “His Jamaatkhana was frequented by Hindu jogis. His langar was open to everyone, irrespective of religious affiliation. Several Jatt tribes of Punjab, like Siyals, attribute their conversion to Islam to the influence of Baba Farid. His shrine was endowed by both the Tughlaqs and the Mughals. Popular lores around his miracles and travels were also widely circulated in Punjab. The establishment of Faridkot is, for instance, attributed to his miracles.”

Prof Banga says that unlike other Sufis in the Suhrawardi order, who would receive grants from the nobility and live comfortable lives, Baba Farid did not approve of patronage. However, for her, his enduring legacy would be his humanistic approach, his concern for the poor and the slaves. “Even though he regarded women as subordinate to men, he conceded some kind of autonomy to those who chose to devote themselves to God or spirituality.” It is this all-embracing attitude of Baba Farid that makes him relevant even today, says Snehi. “He is deeply linked to spiritual lineages of Sufi mystical traditions of South Asia — his spiritual mentor was Qutubuddin Bhakhtiyar Kaki of Mehrauli, Nizamuddin Auliya was his disciple and Sabir Pak of Kaliyar his nephew. All these Sufis are known to have woven a unifying thread of mystical traditions in India.”

US-based Sikh historian Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh says Sheikh Farid’s poetic gems are extremely relevant in our divided society today. “They pull us out of our narrow selfish existentiality, and open up a larger world bustling with diverse religions, races, and cultures. Just as they fill us with empathy for fellow beings (“every heart is a delicate jewel”), they urge us to enjoy the divine One we all have in common.”