Ragmala, lit. a rosary of ragas or musical measures, is the title of a composition of twelve verses, running into sixty lines, appended to the Guru Granth Sahib after the Mundavani, i.e. the epilogue, as a table or index of ragas. In the course of the evolution of Indian music, many systems came into effect, prominent among them being the Saiva Mata, said to have been imparted by Lord Siva, who is accepted as the innovator of music; the Kalinatha Mata, also called the Krsna Mata, which has its predominance in Braj and Punjab and is said to have been introduced by Kalinatha, a revered deity of music; the Bharata Mata, which has its vogue in Western India and was propounded by Bharata Muni; the Hanumana Mata; the Siddha Sarsut Mata; and the Ragaranava Mata.

A large number of ragmalas pertaining to these and other systems that developed are, with some variations, traceable in such well-known works on Indian musicology as Gobind Sangit Shastra, Qanun-i-Mausiki, Budh Parkash Darpan, Sangit Rinaud, and Raga Dipak. With the exception of the Sarsut Mata which subscribes to seven chief ragas, all other systems acknowledge six chief ragas, thirty (in some cases thirty-six also) “wives” or raginis and forty-eight “sons” or subragas, each raga having eight “sons.” Thus each system includes eighty-four measures, which itself is a mystic number in the Indian tradition, symbolizing such entities as the 84 siddhas or the 84,00,000 yoms or species of life.

Though the details concerning the names of “wives” and “sons” differ in each ragmala, the chief systems, broadly speaking, have only two sets: one including Siri, Basant, Bhairav, Pancham, Megh, and Nat Narayan, as in the Saiva and Kalinatha systems; and the other including Bhairav, Malkauris, Hindol, Dipak, Siri, and Megh as in the Bharata and Hanumana systems. In some systems, the ragas have, besides “wives” and “sons”, “daughters” and “daughters-in-law” as well. The chief ragas are suddha, i.e. complete and perfect, while the “wives” and “sons” are sankirna, i.e. mixed, incomplete, and adulterated.

Each of the six principal ragas relates itself by its nature to a corresponding season. The ragmala appended to the Guru Granth Sahib is not much different from the others, and, by itself, does not set up a new system. This ragmala is nearest to the Hanumana Mata, but the arrangement of ragas in the Guru Granth Sahib is nearer to the Saiva Mala and the Kalinatha Mata, which give primacy to Siri Raga. The only system wherein occur all the ragas and raginis employed in the Guru Granth Sahib is Bharata Mata.

In the Guru Granth Sahib no distinction has been made between ragas and raginis; all the measures employed have been given the status of ragas, each one recognized in its own right and not as “wife” or “son” to another raga. In practice, over a long stretch of time, gurmat sangit, i.e. Sikh music, has evolved its own style and conventions which make it a system distinct from other Indian systems. There being no indication to this effect in the caption, the authorship of Ragmala has been the subject of controversy—more so the question of whether it should form part of the recitation of the Holy Text in its entirety. The composition is not integral to the theme of the Guru Granth Sahib, and it has little musicological or instructional significance.

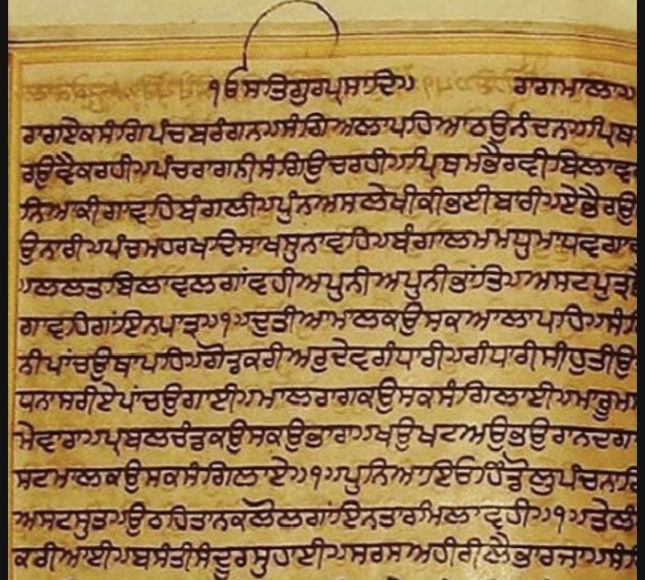

Yet it is entered in the original volume of the Holy Book prepared by Guru Arjan and preserved to this day in the descendant family at Kartarpur. By consensus, Ragmala is taken to be part of the Sacred Text and, with rare exceptions—notably at the Sri Akal Takht—it is included in all full-scale recitations of the Guru Granth Sahib. The Rahit Maryada, the manual of Sikh practices issued under the authority of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, Amritsar, recommends that the reading of the Holy Book be concluded with Mundavani or Ragmala, depending upon local practice, but in no case should the Holy Volume be calligraphed or printed excluding this text.

References :

1. Sabaddrath Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Amritsar, 1964

2. Ashok, Shamsher Singh, Ragmala Nimai. Amritsar, n.d.

3. Kohli, Surindar Singh, A Critical Study of Adi Granth. Delhi, 1961

4. Macauliffe, Max Arthur, The Sikh Religion: Its Gurus, Sacred Writings and Authors. Oxford, 1909

Below is an in‐depth exploration of Ragmala: The Mystical Rosary of Ragas, examining its origins, symbolic significance, and the interplay between music, spirituality, and cosmic order.

Historical Context and Textual Traditions

Ragmala (literally, “garland of ragas”) is a poetic composition traditionally associated with the Guru Granth Sahib. Although its inclusion in the canonical text has been a subject of scholarly debate, its influence is undeniable. In the tradition of Indian classical music, a raga is a musical mode imbued with specific emotional and temporal traits. Ragmala serves as an enumerative and symbolic listing of these ragas, forming a “rosary” where each raga is like a bead that contributes to the overall spiritual harmony of the scripture. This composition has not only musical dimensions but is also considered a cosmic catalog that aligns the Divine Word with the order of the universe .

The Symbolism of a “Rosary” of Ragas

- Garland as a Symbol:

Just as a rosary—a string of beads—serves as a tool for meditation and remembrance in many spiritual traditions, Ragmala offers a chain of musical modes that the devotee may contemplate to internalize the spiritual order. Each raga, named in the garland, stands for a unique set of moods (rasa), seasons, and times of day, suggesting that the universe itself is organized in a tapestry of rhythmic and harmonic patterns. - Unity in Diversity:

The compilation of ragas in the Ragmala emphasizes the belief that while the forms and moods of individual ragas vary, they all emerge from the same Divine Source. This unity amidst diversity reflects a core tenet of Sikh thought—the oneness of God and the interconnectedness of all creation. The garland is symbolic of the cosmic order in which every distinct element contributes to an overarching harmony. - Mystical Ordering of Sound:

In its enumerative function, Ragmala acts as a metaphysical bridge between the tangible performance of music and the intangible realm of spiritual experience. The rhythmic progression through different ragas serves as an allegory for the soul’s journey through various emotional and spiritual states, guiding the devotee toward the realization of divine truth.

Musical and Cosmic Dimensions

- Embedded Wisdom in Musical Modes:

The ragas detailed in the Ragmala not only serve as the basis for musical rendition of Gurbani but also carry intrinsic symbolic meanings. They point to aspects of the natural order—such as time cycles, seasons, and emotional states—which are all considered reflections of the Creator’s design. By aligning one’s inner life with these modes, a devotee is reminded of the eternal and ordered nature of the universe. - Aesthetic and Theological Impact:

The motif of the “garland” unites art, spirituality, and cosmic order. This unification is visibly mirrored in the later Ragamala paintings, where each raga is personified by specific colors, moods, and iconographic symbols. Such works visually capture the essence of these musical modes and reinforce the idea that divine beauty and order pervade every aspect of existence . - Integration within the Guru Granth Sahib:

Even though Ragmala’s canonical status is debated among scholars—with some arguing it may have been a later addition—the symbolism it offers is integral. Whether used as a mnemonic device for the musical modes or as a theological statement on the cosmic reach of the Divine Word, Ragmala encapsulates the Sikh understanding of music as much more than art—it is the pulsating echo of creation itself.

Contemporary Relevance

In modern contexts, the mystique of Ragmala continues to inspire both musicians and spiritual practitioners. It is often cited as an example of how sacred texts integrate artistic expression with divine revelation. The underlying message—that there exists an intrinsic harmony underlying all creation—resonates with contemporary themes of unity, diversity, and the celebration of life’s myriad forms.

Concluding Reflections

Ragmala: The Mystical Rosary of Ragas is not merely a list of musical modes; it is a profound metaphor for the ordered beauty of the cosmos. Each raga, like a bead on a rosary, invites the devotee into meditation, urging one to contemplate the interconnected nature of creation and to rediscover the unity that underlies all diversity. Whether seen as a guide to musical practice or as an allegory for the spiritual journey, Ragmala remains a testament to the timeless fusion of art, music, and spirituality in the Sikh tradition.