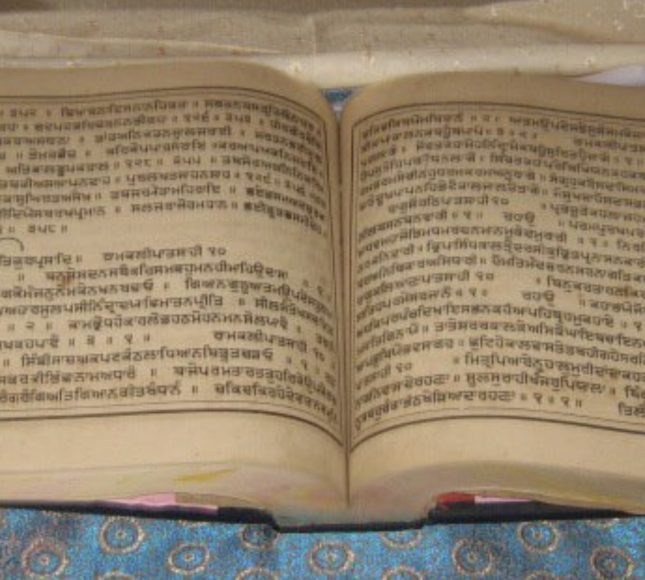

Sastra Nam Mala Puran is a versified composition included in the Dasam Granth. It is acknowledged to be the work of Guru Gobind Singh. The poem lists weapons of war, which are praised as protectors and deliverers. It runs to 1,318 verses and covers 98 pages in the Dasam Granth (24-point 1934 edition). Patshahi 10 is mentioned, although the usual inscription Sri Mukhvak (i.e., from the Guru’s own lips) is absent.

The Sastra Nam Mala was completed in mid‑1687, thus making it one of the earlier compositions—possibly a prelude to the clash of arms that took place at Bhangani the following year. The opening section of 27 verses is an invocation to Sri Bhagautiji for assistance. Here the sword (Bhagautī) is personified as God. God subdues enemies, and so does the sword; therefore, the sword is God, and God is the sword.

In the following arsenal, the weapons of the day are presented under fanciful names—for example, for the arrow: bow-roarer, skin-piercer, deer-slayer, Krsna-friisher; for the mace: skull-smasher; for the combat lasso: death-noose; and the gun is described as the enemy of the army, the tiger foe, the enemy of treachery. Many of the weapons are listed in the form of riddles so dear to the Punjabi heart. These riddles are often abstruse and must be resolved in devious ways. For example:

Think hard and take the word tarangam (stream).

They say ja char (grasseater).

Then think of the word naik (lord).

At the end, say the word satru (enemy).

Lo! Good friend, you have thought of the word meaning tupak (gun). (Verse 811)

The reasoning seems to be that each thing mentioned is the enemy of its predecessor: the grasseater is the deer (where ja is what is produced by the moisture of the stream; char means to graze), the lord and master (naik) of the deer is the tiger, and the enemy (satru) of the tiger is the gun (tupak).

About 25 verses deal with swords of various types, followed by verses concerning spears and the quoit (chakra). There are 178 verses (75,252) on the bow and arrow; on the noose, or combat lasso, 208 (253,460); and on the gun or musket, 858 (4,611,318)—indicating, possibly, an interest in the more modern weapons. Time and again, the weapons are referred to as the instruments of God’s deliverance, and they are addressed as personifications of God. This is sometimes shown in their very names, as when the dagger is called sristes.

Lord of Creation: adoration is reserved for the weapons only when they are used by the righteous. Thus, what might have been merely a gory account of destructive weapons becomes a sharpening of the moral purpose in waging war. The language of Sastra Nam Mala is Braj, with a much lower frequency of Perso-Arabic words than in most of Guru Gobind Singh’s other compositions. Sanskrit vocabulary, in tatsama form, is in abundance. The style is fanciful, and the reader is amazed by the opulence of linguistic innovation.

References:

- Loehlin, C.H., The Granth of Guru Gobind Singh and the Khalsa Brotherhood. Lucknow, 1971

- Ashta, Dharam Pal, The Poetry of the Dasam Granth. Delhi, 1959

- Padam, Piara Singh, Dasam Granth Darshan. Patiala, 1968

- Jaggi, Rattan Singh, Dasam Granth Panchaya. Delhi, 1990

- Randhir Singh, Bliai, Sabadarth Dasam Granth Sahib. Patiala, 1973

Sastra Nam Mala Purān in the Dasam Granth—a remarkable composition that weaves martial symbolism, divine power, and allegorical mysticism into a poetic framework. This text exemplifies the synthesis of spiritual devotion and martial valor in Sikh thought, offering insight both into the metaphysical nature of divine instruments and the practical ethos for the Khalsa warrior.

Introduction and Historical Context

Sastra Nam Mala Purān is attributed to Guru Gobind Singh and occupies a significant place within the Dasam Granth. This versified work, running to over 1,300 verses and spanning nearly 100 pages (in the 24-point 1934 edition), is celebrated for its innovative style and vivid imagery. Traditionally, the text is understood as a prelude to martial engagements such as the clash at Bhangani, reflecting the spirit and preparedness of the Khalsa during tumultuous times. Its historical roots lie in a period when physical prowess and spiritual fortitude were seen as two inseparable aspects of the Sikh ideal.

Divine Instruments and Cosmic Warfare

At the heart of the Sastra Nam Mala Purān is an elaborate mythological narrative in which weapons are not merely tools of earthly combat but are imbued with divine significance:

- Personification of Weapons:

The composition begins with an invocation—27 verses addressed to Sri Bhagautījī—where the sword is exalted to a divine status. Here, the sword is not only a physical weapon but also a manifestation of God’s will. This personification continues throughout the text, as each weapon is praised as an instrument of deliverance and protector of righteousness. - Martial and Mystical Allegory:

The text lists various arms—swords, arrows, maces, loosing devices, and even guns—with each weapon assigned captivating epithetic names such as “bow roarer,” “skin piercer,” and “deerslayer.” Many entries incorporate riddles—a style beloved in Punjabi literary tradition—challenging the listener to decipher connections between terms, where each weapon symbolically represents an aspect of divine activity. In one example, a series of seemingly disparate words is linked allegorically so that the “enemy” of one instrument becomes the precursor to the next, urging the devotee to perceive an underlying order in the martial imagery. - Miri-Piri and the Divine Duality:

The work interweaves the concepts of miri (temporal, martial power) and piri (spiritual authority), implying that true strength emerges from the harmonious union of external defense and inner devotion. In this context, the weapons become metaphors for spiritual virtues—the sword as wisdom that cuts through ignorance, the bow and arrow as focused determination, and so forth—asserting that such divine instruments arise from God’s own play.

Literary Structure and Poetic Style

The Sastra Nam Mala Purān is crafted with a robust mythopoetic language that enhances its dual themes of war and worship:

- Versification and Format:

The composition is arranged in a series of verses that combine classical Sanskrit with the Punjabi diction of the time. Its extensive length (1,318 verses) and elaborate cataloging of weapons showcase a meticulously ordered structure—each entry is rendered not simply as a list but as a stanza imbued with symbolic meaning. - Use of Riddles and Allegory:

An integral feature of the text is its employment of riddles. For example, a verse might invite the listener to “think of the word tarangam (stream)” and then, via a chain of associations, lead them to “tupak (gun)”. Such puzzles demand an active engagement from the reader, emphasizing that true understanding of divine might requires introspection and intellectual as well as emotional insight. - Symbolic Language:

The imagery is vivid and elemental—iron, fire, and steel are recurring metaphors. The title Sastra Nam Mala itself—“the garland of weapons”—suggests that these instruments, when strung together like beads on a rosary, form a complete and unbroken representation of divine power. Each weapon, thus, is not an isolated object but part of an integrated vision of spiritual warfare.

Themes, Moral Purpose, and Spiritual Implications

Beyond the literal enumeration of arms, the text is a meditation on the nature of divine protection and the proper use of force:

- Instruments for Divine Deliverance:

Every weapon listed is presented as an entity endowed with moral authority. When used by the righteous, these weapons defend against injustice and evil; but their sanctity depends on being wielded by those who, like the Khalsa, are spiritually and morally pure. The text, hence, transforms an ostensibly gory account of arms into a teaching on the ethics of warfare and the importance of fighting for a righteous cause. - Transformation of Material Objects:

The Sastra Nam Mala Purān blurs the line between the physical and the metaphysical. What appears as a literally destructive armament becomes, through allegory, an emblem of inner strength and transformation. In this way, the text underlines a critical Sikh teaching: that divine might manifests not only through unyielding physical defense but also through the inner conquest of one’s limitations and the eradication of ignorance. - Preparation for Battle and Spiritual Readiness:

Composed at a time when the Sikh community faced external threats, the text serves as both a call to arms and an exhortation to maintain spiritual discipline. It underscores that the path of the warrior is inseparable from that of the seeker—the martial valor of the Khalsa must always be matched by a deep, abiding commitment to the remembrance of God’s Name.

Enduring Influence and Contemporary Relevance

- Legacy in Sikh Martial Tradition:

The martial imagery and spiritual fervor of Sastra Nam Mala Purān continue to resonate, particularly within the Nihang tradition. For these warriors, the text is not only inspirational literature but a living guide that shapes their identity, rituals, and aesthetic sensibilities. The depiction of weapons as divine instruments reinforces their commitment to defend righteousness while remaining firmly rooted in spiritual ethics. - Modern Interpretations and Artistic Expressions:

Contemporary Sikh scholars, artists, and musicians sometimes reinterpret the text’s allegories, finding in its imagery a metaphor for inner strife and transformation in today’s world. Whether in literary commentaries or visual art, the notion that true power comes from spiritual unity and moral clarity remains a powerful motif that connects past and present. Concluding Reflections

Sastra Nam Mala Purān in the Dasam Granth is a distinctive expression of Sikh martial spirituality—a text where the ephemeral nature of material weapons is transmuted into timeless symbols of divine intervention and inner strength. By elevating physical arms to representations of spiritual virtues, the composition challenges its readers to recognize that true power lies in the integration of the temporal with the transcendent. This enduring message continues to inspire Sikhs to combine the rigor of martial discipline with the serenity of devotional practice, ensuring that each act of defense becomes an act of divine remembrance.