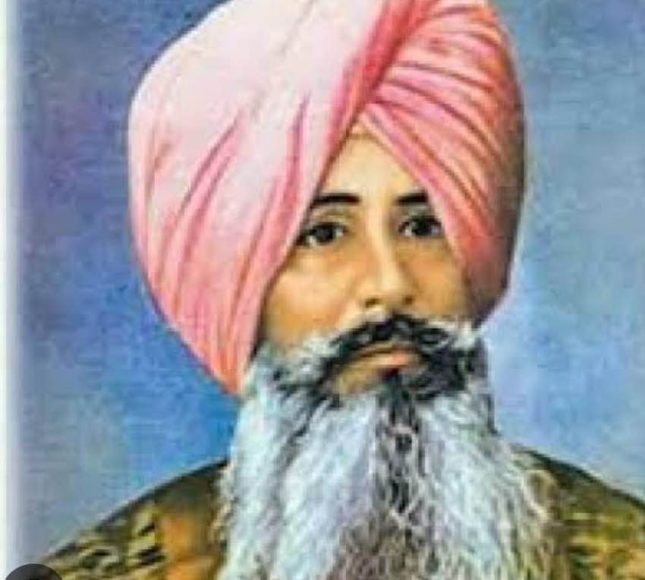

SVAPAN NATAK, lit. dream play, is an allegorical poem in Braj, comprising 133 stanzas, by Giani Ditt Singh, a leading figure in the Lahore Singh Sabha. Published in the supplement to the issue, dated 16 April 1887, of the Khalsa Akhbar, a Punjabi newspaper of which Giani Ditt Singh himself was the editor, the poem led to a defamation suit filed on 14 June 1887 against the author by Bedi Udai Singh, a nephew of the famed Baba Khcm Singh Bedi, leader of the rival Amritsar faction of the Singh Sabha.

Although the author claimed that the poem was produced as a text book with the aim of improving the morals of young men as also of enriching Punjabi literature with the addition of a new category of writing, the composition clearly burlesques several of the men belonging to the Amritsar group. The plot of the Svapan Natak projects the archetypal war between the forces of truth and falsehood culminating in the ultimate triumph of virtue over vice. One of the protagonists of the poem is King Ahankar (i.e. egotism and conceit) symbolizing Raja Bikram Singh, ruler of Faridkot state who was the patron of the Amritsar Khalsa Diwan to which one group of the Singh Sabha was affiliated.

The princely group comprising Baba Kliem Singh Bedi, Mahant Sumer Singh of Patna, Giani Badan Singh of Faridkot, Giani Sant Singh of Kapurthala and others are all referred obliquely and satirically. Giani Jhanda Singh, an employee of Faridkot state, is given the appellation of Mittar Ghat (Slaughterer of Friends) and Bedi Udai Singh who became the complainant in the defamation case, that of Kubudh Mrigesh (Stupid Lion). Khem Singh Bedi himself is referred to in the language of innuendo and given the name of Dambhi Purohit (Hypocritical Priest). The King Ahankar and his friends are pitted against GurmukhJan (i.e. righteous men), allegorically representing Lahore leader, Professor Gurmukh Singh, and his friends.

The campaign is organized in accordance with a scheme hatched by Dambhi, the royal priest, and approved and blessed by King Ahankar. As the battle begins, Badan Manohar (Body Handsome, ironical name for Giani Badan Singh) arrays himself against Sat (truth) and Suhird (sincerity) representing Gurmukh Jan, who are assisted by two women called Bidya (knowledge) and Buddhi (reason). The villainhero fights for the annihilation of the Gurmukh Jan. According to the plan, Manmukh, translated in the court file as a Devil`s disciple, was to murder the believers : Ignorance was to murder Knowledge.

Likewise Folly was to thwart Reason while Kubuddh Mrigesh, the Stupid Lion, was to confound and ensnare the virtuous. The drama has its denouement in the inevitable rout of tlie forces of evil and the victory of the Truth, Knowledge and Reason. A close reading of the poem, however, reveals that it has a complex matrix. It has a polemical end to serve, and here the poet`s powers of caricature and lampoonery come into full play. The poem`s concern with the larger issue of social and religious reform, the central thrust of the Singh Sabha movement, is unmistakable.

In delineating his moral theme, with its personified abstractions, the poet uses a highly allusive diction bristling with puns on the names of the characters, their appearances and their habitual characteristics. The significance of the poem lies in preserving in its line some of the characters of the early days of the Singh Sabha and in the amusement it holds as a literary satire, almost without precedent in Punjabi literature. The defamation case decided by an English judge, W.A. Harris, is also a landmark in the cultural history of the Sikhs. While finding the complaint substantial, the judge decided to award Giani Ditt Singh only a token punishment, obviously impressed by his learning and literary skill.

References :

1. Daljit Singh, Singh Sabha de Modhi Gian Singh Ji. Amritsar, 1951

2. Jagjit Singh, Singh Sabha Lahir. Ludhiana, 1974

3. Harbans Singh, The Heritage of the Sikhs. Delhi, 1983

Svapan Natak: Allegory of Truth vs. Falsehood, an allegorical poem composed in Braj by Giani Ditt Singh—a significant literary figure of the Lahore Singh Sabha. The title “Svapan Natak” literally translates as “dream play,” and through its 133 stanzas the poem presents a vivid, allegorical battle between the forces of truth and falsehood, reflecting the turbulent religious and sociopolitical climate of the late 19th century Sikh reform movement.

Context and Purpose

In 1887, when the Singh Sabha movement was at its peak, debates over religious reform and the proper representation of Sikh values were heated and deeply divisive. Giani Ditt Singh published Svapan Natak as part of the supplement of the Khalsa Akhbar (a Punjabi newspaper), with the declared aim of improving the morals of young men and enriching Punjabi literature with a new category of verse. However, the poem’s satirical and polemical tone—aimed squarely at members of the rival Amritsar faction—soon led to controversy and even a defamation suit by Bedi Udai Singh, a nephew of Baba Khem Singh Bedi. In essence, the poem served as both moral instruction and a pointed critique of factional hypocrisy within the Sikh community.

The Allegory: Truth vs. Falsehood

At its heart, Svapan Natak casts the perennial conflict between truth (Sat) and falsehood (Asat) as an epic battle:

The Forces of Falsehood:

The poem personifies falsehood through the figure of King Ahankar—a symbol of egotism and conceit—which is allegorically linked to historical figures like Raja Bikram Singh of Faridkot. King Ahankar and his cohorts, whose names are rendered in clever, mocking appellations (for example, Giani Jhanda Singh is denoted as Mittar Ghat, meaning “Slaughterer of Friends”, and Bedi Udai Singh appears as Kubudh Mrigesh, or “Stupid Lion”), represent the corrupt and selfserving elements that the reformers sought to expose.

The Forces of Truth:

Counterbalancing these figures, the poem introduces noble embodiments of truth and righteousness—collectively referred to as Gurmukh Jan. In the allegorical battle, these figures are supported by personifications of knowledge (Bidya) and reason (Buddhi), as well as by virtuosos like Sat (truth) and Suhird (sincerity). Their struggle against the deceptive and hypocritical forces is depicted as inevitable and ultimately victorious.

A Polemical Landscape:

The conflict is not only mythic in its proportions but hyperbolically satirical; each character and incident is imbued with symbolic meaning. The villainous strategies—where, for example, a character designated as Manmukh (whom the court file describes as “a Devil’s disciple”) is schemed to murder the personified embodiments of knowledge and reason—underline the central message: falsehood, no matter how cunning it appears, will ultimately be vanquished by the forces of truth.

Literary Devices and Style

Giani Ditt Singh employs a rich blend of allegory, irony, and caricature in Svapan Natak. Writing in Braj, the language of erudite poetry and devotional texts, he combines classical imagery with contemporary political commentary. The dream play format itself allows for a fluid narrative where historical realities, personal rivalries, and moral truths merge into a symbolic theater. With 133 stanzas, the work is meticulously structured to guide the reader through the unfolding drama—a drama that, while entertaining, also carries a clear reformist agenda aimed at questioning and condemning the internal inconsistencies within Sikh leadership.

Impact and Legacy

While Svapan Natak generated controversy in its day, its enduring significance lies in its dual role:

As a Literary Innovation:

It is a pioneering work that introduced a unique genre in Punjabi literature—the allegorical, dreamlike narrative that holds multifaceted symbolic meaning. Its inventive use of allegory influenced subsequent literary forms and served as an exemplar of how poetry can intersect with social and religious critique.

As a Critique of Factional Politics:

The poem reflects the spirit of the Singh Sabha movement’s drive to purify Sikh traditions. By ridiculing the selfserving tendencies of certain religious leaders, it called for a return to the ethical and spiritual foundations laid down by the Gurus. For generations, its allegorical framework has continued to inform discussions on spiritual integrity and communal identity within Sikh historiography.