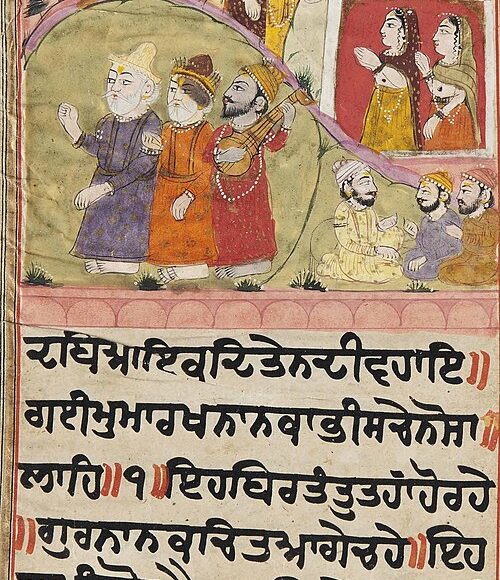

MIHARBAN JANAM SAKHI takes its name from Sodhi Miharban, nephew of Guru Arjan and leader of the schismatic Mma sect. Miharban`s father, Prithi Chand, was the eldest son of Guru Ram Das and as such had greatly resented being passed over as his father`s successor in favour of a younger brother. He set himself as a rival to the Guru. He and his followers who supported his claims were stigmatized as Mmas or hypocrites and out castes.

Succeeding his father as leader of this sect in 1619, Miharban guided it until his death in 1640. Later, the sect declined into insignificance.A belief, however, survived that Miharban had composed a janam. sdkhi of Guru Nanak. Until well into the twentieth century, no copy of this Janam Sdkhi had come to light. The prologue to the highly respected Cyan Ratandvali specifically declared that the Mmas had corrupted the authentic record of Guru Nanak`s life and teachings.

The lost Miharban Janam Sdkhiha.d accordingly been branded spurious and heretical, and but for the Cyan Ratandvali reference it would probably have been forgotten completely.In 1940, however, a Miharban manuscript was discovered at Damdama Sahib and subsequently acquired by Khalsa College, Amritsar. Upon examination this substantial manuscript turned out to contain only the first half of the complete Miharban Janam Sdkhi. According to the colophon, the complete work comprised six volumes (pothis}. The manuscript itself consisted of the first three volumes, Poihi Sachkhand, Pothi Hariji, and Pothi Chaturbhuj, respectively.

The three missing sections were entitled Keso Rdi Pothi, Abhai Pad Pothi, and Prem Pad Pothi. In 1961, the Khalsa College acquired a second and much smaller Miharban manuscript which provided a text for folios missing from the Damdama manuscript. It is, however, limited to a portion of Pothi Sachkhand, and thus provides no material from the three missing volumes.

The only portion to survive from this latter half of the Miharban Janam Sdkhi is its account of the death of Guru Nanak. This has been incorporated in a recension of the Bald Janam Sdkhi tradition. From the extant volumes of the Miharban janam Sdkhi, three important conclusions may l)e drawn. The first of these is that the work can scarcely be described as heretical. Objections grounded in orthodox doctrine may certainly be raised at a few points, but the same can be said of

References :

1. Kirpal Singh, ed., Janam Sakhi Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji. Amritsar, 1962

2. __, Janam Sakhi Parampara. Patiala, 196.9

3. McLeod, W. H., Early Sikh Tradition. Oxford, 1980

The lost Miharban Janam Sakhi Manuscript is a fascinating treasure in Sikh historiography—a substantial work that casts light on one of the earliest narrative traditions concerning the life of Guru Nanak, as told from within the Miharban framework.

A Legacy Born of Controversy and Rivalry

Named after Sodhi Miharban—nephew of Guru Arjan and a leader of a sect that later came to be known as the Mmas (or hypocrites, as his supporters were disparagingly labeled)—the Miharban Janam Sakhi stands apart from the more orthodox collections. Miharban’s lineage, linked with Prithi Chand (the elder son of Guru Ram Das who was passed over for succession), set the stage for a narrative that was as much about a competing claim as it was about chronicling the divine mission of Guru Nanak. For many years, the account attributed to his tradition was dismissed as heretical or at least suspect, a reflection of the deep-seated tensions within early Sikh communities.

The Discovery and Its Content

Until well into the twentieth century, no copy of this Miharban Janam Sakhi had emerged into the public domain. In 1940, however, a significant manuscript was discovered at Damdama Sahib and later acquired by Khalsa College, Amritsar. This substantial manuscript revealed that the complete work was originally composed of six volumes (pothis). The extant manuscript, however, contained only the first three volumes:

- Pothi Sachkhand

- Pothi Hariji

- Pothi Chaturbhuj

According to the manuscript’s colophon, the missing sections were titled Keso Rdi Pothi, Abhai Pad Pothi, and Prem Pad Pothi. These missing volumes would have provided additional layers of narrative and exegesis, but for now, they remain lost to history. Later, in 1961, Khalsa College acquired a second, much smaller Miharban manuscript. This one helped fill in some gaps—providing missing folios from Pothi Sachkhand—but offered no material from the three entirely missing volumes. Remarkably, the only surviving portion from the latter half of the original six-volume work is the account of Guru Nanak’s death, a passage that has been later incorporated into recensions of the broader Janam Sakhi tradition.

Scholarly Impact and Historical Significance

From the manuscripts that do survive, scholars have drawn several important conclusions. First, despite its contentious origins and the sectarian bias against it in later orthodox tradition, the content of the Miharban Janam Sakhi is not overtly heretical. While some doctrinal objections may be raised, many of these mirror disputes already present in early Sikh discourse. Second, the structure and content of the Miharban Janam Sakhi—with its partition into separate pothis and its interweaving of narrative with interpretative discourses (often in the form of gosts)—illustrate the complexity and fluidity of early Sikh literary tradition. It demonstrates how early followers of Guru Nanak sought not only to record monumental events and miraculous signs but also to communicate the transformative, divine quality of his teachings.

This discovery has enriched our understanding of the diversity of Janam Sakhi traditions. It confirms that these narratives, which once circulated orally and were later committed to paper (and lithographic print), played a vital role in forging a sense of unity and personal loyalty among early Sikhs—especially as direct, personal contact with the Gurus became increasingly rare.