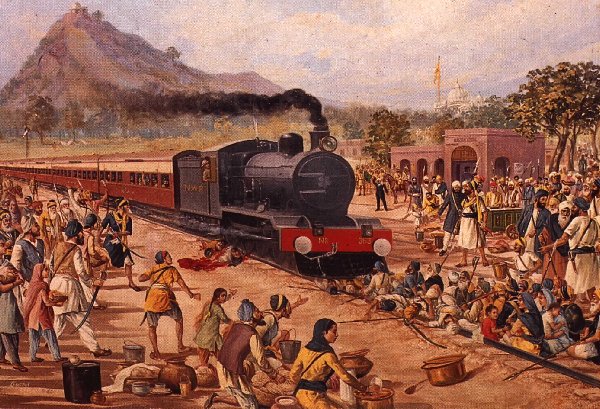

SAKA PANJA SAHIB, the heroic event which took place at Hasan Abdal railway station, close to the sacred shrine of Panja Sahib on the morning of 30 October 1922 and which has since passed into folklore as an instance of Sikh courage and resolution. A nonviolent morcha or agitation to assert the right to felling trees for Guru ka Langar from the land attached to Gurdwara Guru ka Bagh in Amritsar district, already taken over from the priests by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee after a negotiated set dement, had started on 8 August 1922. At first Sikh volunteers were arrested and tried for trespass, but from 25 August police resorted to beating day after day the batches of Sikhs that came.This went on till 13 September when, on the intervention of the Punjab Governor, the beating stopped and the procedure of arrests resumed.

The prisoners were tried summarily at Amritsar and then despatched by special trains to distantjails. One such train left Amritsar on 29 October 1922 for the Attock Fort which would touch Hasan Abdal the following morning. The Sikhs of Panja Sahib decided to serve a meal to the detenues but, when they reached the railway station with the food, they were informed by the station master that the train was not scheduled to halt there. Their entreaties and their plea that such trains had been stopped at other places for the prisoners to be fed went unheeded.

Two of the Sikhs, Bhai Pratap Singh and Bhai Karam Singh who were leading the sangat went forward as the rumbling sound of the approaching train was heard and sat cross legged in the middle of the track. Several others, men and women, followed suit. The train driver slowed down suddenly and brought the train to a screeching halt, but not before it had run over eleven of the squatters. The worst mauled were Bhai Pratap Singh and Bhai Karam Singh, who succumbed to their injuries the following day.

Their dead bodies were taken to Rawalpindi where they were cremated on 1 November 1922. They were hailed as martyrs and, until the partition of 1947, a three day religious fair used to be held in their memory at Pahja Sahib from 30 October to 1 November every year.

References :

1. Ganda Singh, ed., Some Confidential Papers of the Akali Movement. Amritsar, 1965

2. Mohinder Singh, The Akali Movement. Delhi, 1978

3. Teja Singh, Gurdwara -Reform Movement and the Sikh Awakening”. Jalandhar, 1922

4. Sahni, Ruchi Ram, Struggle for -Reform in Sikh Shrines, Ed. Ganda Singh. Amritsar, n.d

5. Pratap Singh, Giani, Gurdwara Sudhar arthat Akali Lahir. Amritsar, 1975

6. Josh, Sohan Singh, Akali Morchian da Itihas. Delhi, 1972

The tale of Saka Panja Sahib unfolds as a stirring narrative of unwavering determination, selfless service, and nonviolent defiance. During the early 1920s—a time marked by struggle and a growing desire for reform within the Sikh community—the seeds of courage were sown amid the challenges of the colonial era. It was in this complex context that a group of inspired Sikh volunteers embarked on a resolute mission at Hasan Abdal railway station, near the revered shrine of Gurdwara Panja Sahib, to stand against injustice and provide desperately needed aid. Their brave act of stopping a train carrying Sikh prisoners, whose detentions were tied to the disputes surrounding the Gurudwara Guru Ka Bagh, became a defining moment in Sikh history.

On the fateful morning of October 30, 1922, as the train approached with its burden of arrested comrades, Sikh volunteers moved deliberately onto the tracks. Realizing that the act of serving langar (a community meal) was more than feeding hungry souls—it was an expression of universal dignity and the deep-rooted Sikh commitment to seva—they chose to block the passage of the train. When two resolute figures, Bhai Pratap Singh and Bhai Karam Singh, led the demonstration, their physical presence on the rail line became a dramatic stand against authority. Even as the train neared, despite warnings and the inherent danger, these heroes remained unmoved, echoing the eternal Sikh spirit that holds firm in the face of potential martyrdom.

The ensuing moments were tragic yet transformative. The train, forced into a sudden halt by the unwavering protest, could not avoid the deadly consequences. As it released a cascade of crushing force, several of the courageous protestors were fatally injured. Their sacrifice transcended the immediate sorrow of loss—it resonated as a powerful symbol of nonviolent protest and martyrdom in the struggle against systemic oppression. The valor of these individuals, who chose death over submission, reverberated across the community, inspiring a legacy of resistance imbued with dignity, self-respect, and the relentless pursuit of justice.

Today, the legacy of Saka Panja Sahib endures as an enduring wellspring of inspiration for Sikhs and other communities who value justice, courage, and service. The memory of these martyrs is commemorated not merely as a historical event, but as a living testament to the transformative power of collective courage. Their act reminds us that extraordinary sacrifice can illuminate even the darkest of times and that the spirit of nonviolence, when grounded in deepest values, transcends the boundaries of time and place. This saga invites us to reflect on our own commitments to struggle for what is right and the potential each act of defiance has to spark change.