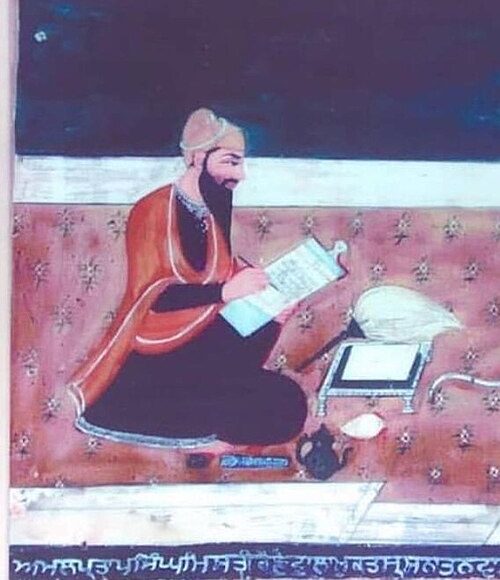

BHAGAT MAL, subtitled Sakhi Bhai Gurdas Ji ki Var Varan Sikhan di Bhagatmala, is an anonymous manuscript (Kirpal Singh, A Catalogue of Punjabi and Urdu Manuscripts, attributes it to one Kirpa Ram, though in the work itself no reference to this name exists) held in the Khalsa College, Amritsar, under MS. No. 2300, bound with several other works all of which are written in the same hand. The manuscript comprises 83 folios and is undated. The opening page of the full volume, however, carries the date 1896 Bk/AD 1839 which may be the year of its transcription. Bhagat Mal is a parallel work to the more famous Bhagatmala by Bhai Mani Singh and is, like the latter, meant to be an elaboration of Bhai Gurdas`s eleventh Var, listing the more prominent of the Sikhs of Guru Nanak`s time.

All the 30 stanzas of the Var are reproduced each with explanation under the heading tisda vfchar (explanation of that). First 12 stanzas contain no names: they are devoted to elaborating the theory of Sikhism and the characteristics of an ideal Sikh and his mode of living. From the 13th stanza onward (f. 260), the names of various Sikhs are given. Under “explanation,” a question is put forward by a Sikh pertaining to the principles and practices of the Sikh faith such as seva, selfless, voluntary service, charity, control of mind, remembrance of God, home life, lust, and anger.

Occasionally, some questions relate to philosophical issues as well, for instance, whether God is transcendent or immanent. At places incidents from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as well as hymns from the Guru Granth Sahib are quoted to illustrate a point. Some contemporary events from Sikh history such as the construction of the temple and the tank at Amritsar and the compilation of the Adi Granth are also referred to. At folio 325, Bhai Nand Lal is quoted as saying that the Guru bestowed all honour on the Khalsa adding that Sahajdharis were also accepted along with Kesadharis.

Historical Background and Attribution

The Bhagat Mal Manuscript is traditionally linked with the corpus of Sikh bhagat literature—a category of writings composed by saints other than the Sikh Gurus. In several scholarly circles, the work is connected to the legacy of Bhai Mani Singh (d. 1737), whose name was invoked in various manuscripts to lend authority to these texts. One of the most intriguing sections associated with this manuscript is the “Wajab ul-Arz,” a ten-point petition reportedly addressed to Guru Gobind Singh by Sikhs who embraced his teachings yet had not been formally inducted into the Khalsa. Although original copies of these manuscripts met a tragic fate during periods of violent upheaval (notably Operation Blue Star in 1984), their content survives through prints and critical editions, revealing a complex tapestry of historical memory and devotional practice .

Core Themes and Content

The Bhagat Mal Manuscript and its related texts offer several layers of insight:

- Negotiating New Religious Norms:

At the heart of the manuscript lies a spirited debate about the practical challenges that followed Guru Gobind Singh’s establishment of the Khalsa on Baisakhi 1699. For instance, certain passages reflect a tension regarding the shift away from traditional Brahmanical practices. One petition posed questions such as whether Sikh converts should continue to involve Brahmins in marriage ceremonies or conducting funerary rites, contrasting these practices with the new ideals that emphasized autonomy from older caste-based rituals. In essence, the manuscript captures a moment when early Sikhs were actively negotiating their identity, delineating what it meant to be both modern and faithful in a rapidly changing spiritual landscape. - Interweaving of Literary Traditions:

The manuscript is not confined to a single linguistic or cultural tradition. It often blends Hindi, Punjabi, Sanskrit, and Persian expressions while being transmitted in the Gurmukhi script. Such hybridity testifies to the manifold influences during the period and illustrates how Sikh textual production was both a continuation of older Indic literary practices and an innovative response to new spiritual imperatives. Notably, later commentaries—for example, as seen in collections like the Ath Sri Gur BhagatMal Granth Steek—highlight how these texts sometimes draw parallels with Hindu mythology, even as they narrate the spiritual journey of the Sikh Gurus (). - A Tool for Community Formation:

By laying out detailed petitions and responses regarding ritual conduct and community norms, the Bhagat Mal Manuscript served a practical function. It was an instrument intended to clarify ambiguities in practice among those who followed Guru Gobind Singh’s teachings. The petitionary format, with requests for the Guru’s signature on its answers, was designed to lend irrevocable authenticity to the prescriptions of the emerging Khalsa order—strengthening communal resolve and identity in the process. Scholarly Implications and Cultural Resonance

The insights derived from the Bhagat Mal Manuscript are manifold:

- Ritual and Identity Formation:

The manuscript helps us understand how early Sikh communities devised strategies to establish clear boundaries between the traditional practices of the past and the new codes of conduct. Its reflections on ritual prescriptions illuminate the practical challenges that came with religious reform and the redefinition of social roles within the Sikh fold. - Intellectual Exchange and Syncretism:

The text’s intertextual references—with extensive quotations drawn from older Hindu scriptures—showcase the dynamic intellectual interplay prevalent in Sikh literature of the time. In engaging with Vedantic and other Indic philosophies, the manuscript not only argues for a distinct Sikh identity but also demonstrates the syncretic nature of the spiritual dialogues that characterized the region. - Preservation Amid Turbulence:

The tragic loss of many manuscript copies during periods of conflict underscores both the preciousness of such texts and the challenges inherent in preserving pre-modern literature. Modern digital archiving and textual analysis are now offering renewed hope in restoring and reinterpreting these handwritten treasures, ensuring that their insights continue to inform contemporary debates on identity, ritual, and rebellion.