SALOK MAHALLA 9, i.e., slokas of the composition of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Nanak IX, form the concluding portion of the Guru Granth Sahib, preceding Guru Arjan’s Mundavani (GG, 1426–29). These slokas are intoned as part of the epilogue when bringing to a close a reading of the Guru Granth Sahib on a religious or social occasion and should thus be the most familiar fragment of it, after the Japji, Sikhs’ morning prayer. Slokas, in Sanskrit, signify a verse of laudation. In Hindi and Punjabi, it has come to imply a couplet with a moral or devotional content. Its metrical form is the same as that of a doha or dohira, a rhymed couplet.

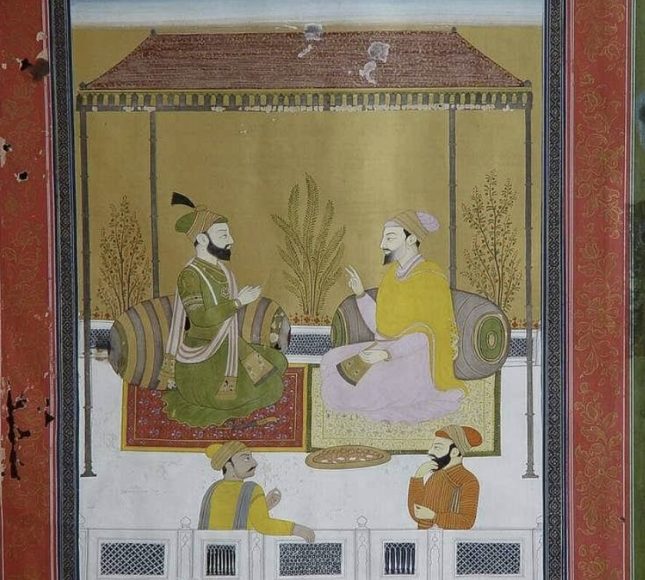

Guru Tegh Bahadur’s slokas, 57 in number, were incorporated into the Guru Granth Sahib by Guru Gobind Singh. As is commonly believed, they were composed by Guru Tegh Bahadur while in incarceration in the kotwali, in the Chandni Chowk of Delhi, before he met with a martyr’s death. Whether the slokas were written during the days just before Guru Tegh Bahadur’s execution or earlier in his career as some say, their mood is certainly in consonance with the crisis of that time, when the Guru confronted the imperial might of the last great Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb, to defend the freedom of religion and worship in India and gave his life for a cause which, to him, meant true commitment to God. The message of the slokas is fundamentally the same as that of the rest of the Sikh scripture.

Here, as everywhere else in the Guru Granth Sahib, the stress is on remembrance and contemplation of God and recitation of Nam, i.e., God’s Nam. To quote the opening sloka:

*To the praise of God you have not lent yourself,

Your life you have thus wasted away.

Says Nanak, cherish God’s *Nam* in your heart,

As the fish cherishes water.*

The same message is repeated almost in every other line. The underlying assumption is that God, referred to by various names such as Gobind, Ram, Hari, Bhagvan, is the only true reality and the source of all existence.

Everything except God is a passing phenomenon. Since all things of the world, no matter how much sustenance and satisfaction they may appear to give, must pass, there is nothing permanently valuable in them. Their value, as well as their existence, is ultimately derived from the eternal source of Being, God. It is, therefore, shortsightedness to seek lasting happiness in worldly things as such, without realizing that the happiness we associate with them does not proceed from them but from God.

On the other hand, since prayer and contemplation on the Nam are the means to God-realization, the enjoyment of the ephemeral things of the world, accompanied by these, becomes an enjoyment of the perennial Divine Reality. Without constant remembrance of the Divine Nam, such enjoyment remains absorption in merely short-lived things and is, therefore, bound to end in grief. While advocating devotion to God, the slokas also preach detachment from worldly pleasures. The need for detachment is a theme as important and as closely intertwined with the importance of prayer as it is in other parts of the Guru Granth Sahib.

The argument for detachment is the unreliability of the world. The slokas unremittingly depict the fickleness and inconstancy of all that most of us ordinarily seek and cherish in life—material possessions, power and authority, love and loyalty of friends and relations, strength of limbs and faculties. The focus is on the short-livedness and transience of human life. Life passes all too soon, youth being quickly replaced by decrepitude and senility.

Blind to reality and overconfident of our strength, most of us continue to spend ourselves in mundane pursuits and remain oblivious of God. A life completely devoted to worldly pursuits is a life spent in delusion—unreality taken for reality. The vanity of worldly things and the attitude of renunciation seem to be much more pronounced in the slokas than anywhere else in the Guru Granth Sahib. Yet in keeping with the spirit of the entire gurbani, this feature of the slokas does not imply a rejection of life.

On the contrary, the message is one of a strong affirmation of human life. The advice is not to renounce living, but only to give up wrong living. That life should be lived right and not wasted in wrong pursuits clearly indicates a belief in its intrinsic worth. The essence of the teaching here is that one should not cling to life indiscriminately without regard to right or wrong.

It is such loss of discrimination that robs life of its meaning and makes it worthless, even evil. Lived right, life is meaningful and precious. To follow good in the world and to renounce only that which is opposed to good is the essential lesson of the slokas. While the slokas advocate detachment, there is also implicit in them the advice to be involved with the world. Detachment is enjoined because the evanescent world provides no basis for building anything permanent in it. But, at the same time, there is a deep concern for accomplishment and for full use of one’s time and energy to do so.

Regret over time lost without significant achievement is a sentiment as strongly and frequently expressed as the tendency towards aloofness. The best use of time is to devote it to remembering God. But contrary to what might be assumed, immersing oneself in Nam Simran does not mean withdrawal from the world but contemplation of God in the midst of it. It does not imply an ascetic life; it does not necessarily require the abandonment of things that yield common pleasures and satisfactions.

These things are given by God. God’s gifts cannot but be good and their enjoyment wholesome. We should be grateful for them. Our lack of gratitude is to be deplored. Only when worldly things are considered sufficient in themselves and God is forgotten does attachment to them become unwholesome.

Otherwise, acceptance of the world is essential to godliness. The slokas comprise some of the most moving poetry in the Guru Granth Sahib. Their music, imagery, and other poetic features combine to capture the experience of life with lyrical intensity. The music of the slokas can be appreciated only in reading or listening to them in the original.

There is in this music a quality that makes one sad and is yet very charming to the ear and soothing to the soul. It arouses a keen awareness of the tragic in life and at the same time allays the pain of this awareness. Only a few examples need be cited here in order to convey the poetic quality of the slokas:

As a bubble on water, momentarily appears and bursts, The same is the way the world is made; Remember this, my friend, says Nanak!

Head shaking from old age, steps infirm, eyes devoid of light; Says Nanak, this is the state you have come to, Yet you seek not the joy from God flowing.

False, utterly false, is this world, my friend, Know this as the truth; Says Nanak, it stays not, as stays not a wall made of sand.

Here is poetry that strongly evokes the fleeting spectacle of human existence. It fills the mind with deep thoughts, producing a mood in which all fretfulness about worldly gains or losses in a fundamentally unstable world seems utterly senseless. The effect is not lassitude. Instead, the mind is released from all those oppressive feelings such as anxiety, despair, and grief which the setbacks and difficulties of life generally bring with them. An inner peace prevails, giving intimations of abiding self and reality as perennial reservoirs of security accompanying one in the passage through an impermanent world. A renewed commitment to life, in spite of life’s limitations, is the gentle yet powerful message of the slokas.

References:

- Sabadarth Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Amritsar, 1969

- Sahib Singh, Sri Guru Granth Sahib Darpan. Jalandhar, 1962–64

- Kohli, Surindar Singh, A Critical Study of Adi Granth. Delhi, 1961

- Macauliffe, Max Arthur, The Sikh Religion: Its Gurus, Sacred Writings and Authors. Oxford, 1909

- Harbans Singh, Guru Tegh Bahadur. Delhi, 1994

Salok Mahalla 9—the slokas composed by Guru Tegh Bahadur (often referred to as Nanak IX), which form the concluding portion of the Guru Granth Sahib before Guru Arjan’s Mundavani. These couplets, rich in spiritual and moral insights, have long been recited as a capstone during the ceremonial reading of the Sikh holy scripture. Let’s delve into their historical context, structure, themes, and enduring impact.

Historical Context and Composition

- Authorship and Incorporation:

The 57 slokas of Salok Mahalla 9 were composed by Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh Guru, and subsequently incorporated into the Guru Granth Sahib by Guru Gobind Singh. Traditional accounts suggest that these slokas were written during Guru Tegh Bahadur’s incarceration in the kotwali (prison) at Chandni Chowk, Delhi, in the turbulent days preceding his martyrdom. Whether they were penned shortly before his execution or composed earlier in his spiritual journey, their tone is unmistakably reflective of the crisis and determination of that era—a period marked by the Guru’s courageous defiance of Mughal religious persecution under Emperor Aurangzeb. - Historical Significance:

In the face of imperial oppression and the struggle for religious freedom, Guru Tegh Bahadur’s verses resonated deeply with the Sikh community. They encapsulate a spirit of resolute faith and moral clarity, simultaneously echoing the call to defend the sanctity of individual worship and reminding adherents that true commitment lies with the Divine, not with transient worldly power.

Structure and Poetic Form

- Form and Meter:

The Salok Mahalla 9 is composed in the form of couplets—each slok is essentially a doha or dohira, a traditional rhymed couplet structure common in classical Indian poetry. This metrical form, with its balanced rhythm and concise expression, lends the saloks both memorability and a musical quality that enhances their recitation. - Placement within the Canon:

These slokas occupy pages 1426 to 1429 of the Guru Granth Sahib and serve as the final segment of the main text, immediately preceding the Mundavani (epilogue). Because they are used during the closing rites of sacred reading (Bhog) on religious and social occasions, they have become among the most familiar and frequently recited fragments of the scripture—second only to the Japji Sahib, which is the cornerstone of the morning prayers.

Themes and Spiritual Message

- Remembrance of the Divine:

A central tenet of the saloks is the unwavering call to remember and contemplate God (Nam). Guru Tegh Bahadur’s verses remind the devotee that God—referred to by various names such as Gobind, Ram, Hari, and Bhagvan—is the only true reality and the eternal source of all that exists. By urging one to cherish God’s nam in one’s heart (as vividly illustrated in the opening couplet comparing the devotion of a fish to water), the saloks stress that true fulfillment lies in a life illuminated by divine remembrance. - Impermanence of the World:

The saloks underline the transient nature of worldly life and material pursuits. They assert that no matter how substantial the pleasure or security provided by worldly gains appears, all is ephemeral. In contrast, the divine reality offers permanence and lasting happiness. This recognition calls for a balanced perspective: while one must live life fully and responsibly, attachment to impermanent things only leads to sorrow. - Detachment and Right Living:

Integral to the message is the theme of detachment—not as a call for complete renunciation of the world, but as an instruction to distinguish between what is enduring (the Divine) and what is fleeting. The saloks convey that one should never invest total happiness in worldly achievements; instead, one should cultivate a disciplined life that involves both engagement with the world and an inner detachment. By renouncing “wrong living” (characterized by ego, greed, and material obsession), one can uphold a life of virtue and moral clarity. - Call for Discernment:

The slokas encourage the devotee to exercise discrimination in their pursuits. They warn against clinging to life indiscriminately—emphasizing that the loss of discernment robs life of meaning. When lived correctly, however, life becomes precious and filled with purpose. This dual message of detachment and active, righteous engagement offers a holistic pathway to personal and spiritual fulfillment. - Emotional and Poetic Expression:

The imagery used in the saloks is vivid and poignant. Metaphors—such as comparing the fleeting nature of life to a bubble that appears briefly on water before bursting or a wall made of sand that cannot withstand the passage of time—evoke a deep awareness of life’s transient nature. This lyrical beauty not only serves an aesthetic function but also reinforces the philosophical message: all worldly things must pass, and only the remembrance of God provides lasting solace and security.

Poetic and Musical Qualities

- Lyrical Intensity:

The verbal cadence of Salok Mahalla 9 is both melancholic and inspiring. Its music, inherent in the rhythmic couplets, carries an emotional complexity that makes one both aware of the tragic nature of human existence and uplifted by the promise of inner peace. The verses are best appreciated in their original language, as their musicality and subtle nuances often lose something in translation. - Universal Appeal:

Even beyond the specific historical context of persecution and martyrdom, the poetic qualities of the saloks have a universal resonance. Their meditative tone, combined with the stark reminders of life’s impermanence, appeals to anyone grappling with the tension between temporal attachments and the pursuit of eternal values.

Enduring Impact and Contemporary Relevance

- Liturgical Role:

In Sikh practice, the recitation of Salok Mahalla 9 as part of the Bhog (concluding reading) reinforces its role as a spiritual reminder at the end of communal worship. Its integration into daily recitations ensures that the ethical and metaphysical lessons encapsulated in its couplets continue to guide the community. - Moral and Spiritual Guidance:

The saloks, with their emphasis on discerning right from wrong and detaching from material illusions, serve as a constant reminder to live a disciplined life rooted in faith and compassion. They challenge individuals to test their own attachments and to prioritize the eternal over the transient—a message as relevant today as it was in the days of Guru Tegh Bahadur. - Legacy of Guru Tegh Bahadur:

The inclusion of these slokas in the Guru Granth Sahib by Guru Gobind Singh not only preserved Guru Tegh Bahadur’s legacy of courage and unwavering commitment to religious freedom but also enshrined his spiritual insights for generations. For many, Salok Mahalla 9 offers a window into the inner life of a Guru who faced immense trials yet remained steadfast in his devotion to the eternal truth. Concluding Reflections

Salok Mahalla 9 stands as a profound and multifaceted composition—both a poetic masterpiece and a beacon of spiritual wisdom. It encapsulates the essence of Sikh teachings by urging constant remembrance of the Divine, advocating for the discernment between transient worldly allurements and everlasting spiritual fulfillment, and fostering a balanced life of active engagement combined with inner renunciation. The slokas remind us that while the material world is ever-changing and ephemeral, the divine light remains constant—a source of unlimited comfort and strength for those who choose to live in awareness of it.