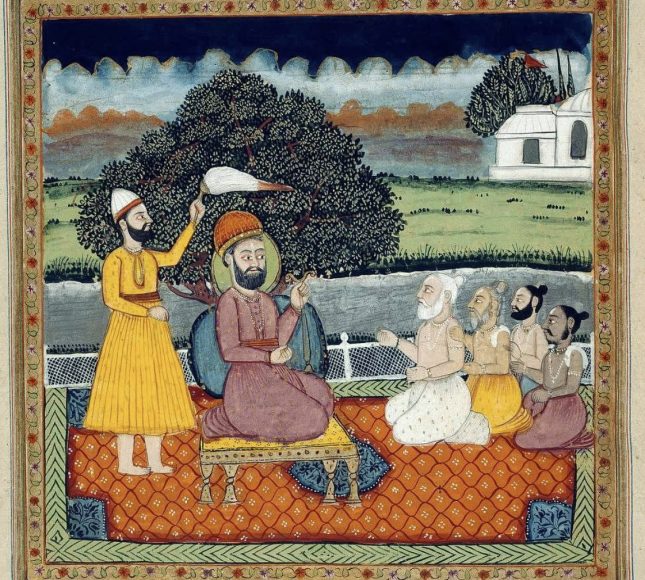

SIDH GOSTI, i.e. discourse or dialogue with the Siddhas or mystics adept in hatha yoga and possessing supernatural powers, is the title of one of Guru Nanak’s longer compositions recorded in the Guru Granth Sahib. A goshti (gosti) seeks to expound the respective doctrines of scholars or saints participating in it, revealing in the process their dialectical prowess and learning. In the Sidh Gosti all the questions are raised by the Siddhas and all the answers come from Guru Nanak. It strikingly brings out the crux of his teaching, especially in relation to the Siddhas’ philosophy and way of life.

The text itself does not provide any clue as to the time and place of its composition, though it is generally placed in the last years of Guru Nanak’s life when he had finally settled down at Kartarpur after completing his major preaching odysseys. Moreover, the composition might not be the record of any of the goshtis that are said to have occurred at Gorakh Hatri, Gorakh Mata (also known as Nanak Mata), Sumer Parbat, and Achal Batala, but rather a recollection in tranquillity of the major points from various discourses between Guru Nanak and the Siddhas at these or other places. The Sidh Gosti comprises seventy-three stanzas, of which the first stanza—consisting of four lines—is presented as a prologue wherein Guru Nanak is depicted discoursing with the Siddha Sabha (i.e. assembly of the Siddhas), proclaiming that he paid obeisance to none other than the True Infinite One, before whom everybody bows and who can be realized only with the aid of a spiritual preceptor.

Guru Nanak states that meditation on His Name is the only way to liberation and that the outer garb and wandering in search of Him are futile. After the first stanza in this section, there is a couplet marked as rahau, or pause, which sums up the substance of the whole composition: renouncing the world and wandering in woods and mountains will be fruitless; it is through the True Name that life becomes pure and purposeful and one can attain emancipation. The three stanzas, numbered four to six, are designed as Guru Nanak’s discourse with Charpat, who belonged not to the Siddha tradition but to the Natha tradition—which had evolved in protest against the former’s over-infatuation with supernatural powers generally used for the satisfaction of carnal desires. Charpat poses two questions to Guru Nanak on how one can successfully swim across the ocean of life and how to realize God.

Guru Nanak’s reply is that one can achieve liberation by remaining detached while still living in the world and by making the human heart a worthy abode for the Supreme Being through the cleansing of all impurities, rather than by renouncing the world as did the Siddhas, Nathas, and Yogis. Stanzas seven to eleven comprise Guru Nanak’s dialogue with Loharipa, who proclaims the importance of renunciation, outer garbs, and rituals—in contradistinction to Guru Nanak’s stress on inner purity and self-control. Loharipa favors the austere life of Siddhas, who lived amid shrubs and trees, away from the towns and highways, subsisting on roots and underground bulbs. According to him, ablutions at a sacred place of pilgrimage brought man peace.

Guru Nanak rejects the significance of outer garb and the renunciation of the world in favor of wandering in forests away from human habitation and visiting places of pilgrimage as the ultimate end of human life. Instead, he recommends that man control his passions and fix his mind on Him who pervades the universe, for the universe is His creation. What follows in stanza eleven is not Guru Nanak’s discourse with any particular Siddha, but his recollection of several points from dialogues he might have had with different Siddhas on various occasions. These cover a wide variety of subjects such as the definition of a true yogi, gurmukh (one whose face and mind are turned towards the Guru) and manmukh (the self-willed), the origin of the universe and of man, and the significance of truthfulness and constant meditation on His Name in realizing the ultimate end of human life—that is, emancipation from the cycle of transmigration and union with the Supreme Being.

According to Guru Nanak, a yogi is not one who renounces the world and wanders in the woods and mountains, but one who effaces his self-conceit, becomes detached, and enshrines the True Lord in his heart. As opposed to a manmukh, i.e. one who is self-willed and, assailed by doubt, wanders in the wilderness (26), a gurmukh—one whose face and mind are turned towards the Guru—remains busy reflecting on the gnosis and attains the invisible and infinite Lord (27). In answering the Siddhas’ questions concerning the origin of the universe and man, Guru Nanak also refers to the concepts of sunya (void) and sabda (word).

Before the creation of man and the universe, there was no world, no firmament, yet it was not an empty void. The Light of the Nirankar (i.e. the Formless Lord) pervaded the three worlds (67). Guru Nanak’s sunya, rendered as “sunn” in the text, does not mean nothingness or an empty void. It is not a negative concept; rather, it is a positive cause of the cosmos—it is nothing but the Brahman Himself. His sunya is likened to the emptiness of a vase, representing the essential intrinsic nature and quality of the pot. The term has also been used in the sense of Brahman, both as Brahman with maya and as pure Brahman, when the Guru states that sunya is within us and without us, and that the worlds are also imbued with sunya.

He who realizes the fourth state of sunya remains unaffected by vice and virtue (51). Here, the sunya that envelops the three worlds is nothing but Brahman with maya, while the fourth state of sunya is pure Brahman. In reply to a Siddha’s question as to how sunya (i.e. Brahman) is obtained and what the state is of those who are imbued with sunya (the Lord), Guru Nanak replies that it is through the Guru—and by instructing the mind—that the Imperishable Lord is obtained. Those who obtain Him become like Him, from whom they have emanated, and they suffer not the cycle of transmigration (52). A person who understands the mystery of God, who pervades all hearts, becomes himself the manifestation of the Primal, Immaculate, and Luminous Lord; one imbued with His Name is himself the Lord Creator (51).

The sabda, which in Gurbani has been described more in terms of what it does than what it actually is, provides the means whereby man can know both God and the path that leads to Him—the means whereby man may secure release from bondage and attain union with Him. In Sidh Gosti, sabda (or sabad) is equated with enlightenment, eternal delight, and true yoga (32 and 33). Sublime understanding and the shedding of lust, anger, and ego are possible only with the help of sabda (10). It is through sabda that man is able to counteract the poison of ego and understand the true meaning of creation and of the Creator (21).

Furthermore, sabda is competent to annul man’s transmigration and secure him liberation (25). All the wanderings of yogis and sannyasis will come to naught if they fail to drop ego from their hearts (34), and ego—which hinders man’s progression towards the Supreme Reality—can be effaced only through sabda (21). In reply to a Siddha’s question regarding the abode of the sabda that helps man ferry across the ocean of life (58), Guru Nanak says that it pervades all beings and, if one is blessed with the Lord’s grace, it abides in the human heart, dispelling all doubt and leading one to union with the Supreme Lord (59).

The language of the Sidh Gosti is Sadh Bhakha, laced with an admixture of technical terms from the disciplines of the Yogis and the Siddhas. Brevity is the chief characteristic of the style of expression. The symbols and metaphors used are more functional than decorative and have been drawn from everyday life. For example, the classical symbol of a lotus flower growing in water—drawing its sustenance from the mud below yet remaining untouched by it—has been used to illustrate that man can live a detached life in this world and realize the Supreme Lord by enshrining His Name in his heart. Similarly, the symbol of a duck swimming in water without wetting its wings is employed to the same effect.

References:

- Sabadarth Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Amritsar, 1962

- Gurdas, Bhai, Varan. Amritsar, 1962

- Jodli Singh, The Religious Philosophy of Guru Nanak. Delhi, 1983

Guru Nanak’s Sidh Gosti: A Dialogue of Wisdom—a cornerstone composition of the Guru Granth Sahib that encapsulates Guru Nanak’s method of engaging in a spiritual dialogue with the Siddhas (mystics) of his time. This poetic discourse not only articulates his visionary philosophy but also challenges and redefines the limits of traditional ascetic practices.

Literary Form and Context

- A Poetic Dialogue:

Sidh Gosti (or Sidh Gosht) is presented as a dialogue—a goshti—between Guru Nanak and a group of Siddhas, renowned mystics and yogis who were steeped in hatha yoga and supernatural pursuits. The term “goshti” itself indicates a conversational format where questions are posed by the Siddhas and answered with clarity and insight by Guru Nanak. Traditionally, this composition is believed to date from the final years of Guru Nanak’s life, when, settled at Kartarpur, he reflected on the essence of his spiritual engagements. - Structure and Composition:

The text comprises 73 stanzas, with the first stanza serving as a prologue. In these verses, Guru Nanak establishes the fundamental premise of his message: he pays homage to the One True, Infinite Lord, invoking a vision of a reality accessible through inner awakening rather than through the esoteric practices of traditional yogic orders. The literary style is marked by simplicity, economy of language, and metaphorical richness—a blend of Gurmukhi idiom with elements that recall classical Sanskrit and regional dialects.

Themes and Philosophical Insights

- Transcending Ritual and Supernaturalism:

One of the primary themes of Sidh Gosti is the dismantling of the prevailing notion that external asceticism and the pursuit of supernatural powers (siddhis) are the keys to enlightenment. While the Siddhas inquire about the practices and attainments associated with their traditions, Guru Nanak counters with the idea that true liberation comes solely through devotion to— and remembrance of—the Divine Name (Naam Simran). This radical reorientation shifts the focus from esoteric practices to inner transformation. - The Centrality of Divine Love and Remembrance:

Throughout the discourse, Guru Nanak emphasizes that the essence of spiritual realization is not in wandering through varied ascetic rituals or accumulating mystical powers, but in cultivating a deep, heartfelt connection with the Divine. The dialogue repeatedly returns to the motif that the external trappings of asceticism are futile unless one establishes an intimate relationship with God. The Siddhas’ questions and his answers together create a dynamic interplay that foregrounds loving surrender, humility, and continuous meditation as the true means to overcome the limitations of the ego. - Critique of Empty Mysticism:

Sidh Gosti also functions as a subtle critique of the ideologies prevalent among many yogic traditions of the time. Guru Nanak points out that mere physical austerities or miraculous feats—often celebrated in Nath and Siddh traditions—do not secure liberation. Instead, he argues, what matters is the inner illumination that comes when one discards ego and embraces the eternal truth. This message resonates with his larger ethos of rejecting both sectarian ritualism and the exclusive pursuit of supernatural accomplishments. - Dialogue as the Medium of Revelation:

The structure of the dialogue itself is instructive. By engaging with the Siddhas’ queries, Guru Nanak not only demonstrates his dialectical prowess but also reveals the core of his teaching: the realization of the Divine is accessible to everyone regardless of background, provided they open their hearts and minds. In this exchange, the traditional authority of the Siddhas is respectfully questioned, allowing his vision of a more practical, inclusive, and humane spirituality to take center stage.

Spiritual Impact and Legacy

- A New Paradigm for Spiritual Practice:

Sidh Gosti redefines the path to liberation by insisting on love, humility, and the continuous remembrance of God’s Name as the ultimate remedy for the sufferings of life. By dismantling the barriers of rigid asceticism, Guru Nanak’s discourse laid the foundation for a spiritual practice that is accessible, internal, and deeply personal—a hallmark of Sikh thought. - Interfaith Engagement and Inclusive Wisdom:

Although framed as a dialogue with mystics from an earlier tradition, the composition transcends the boundaries of any single school of thought. It offers a universal message that speaks not only to Sikhs but also to seekers from diverse spiritual backgrounds. The emphasis on inner realization and the critique of empty rituals continue to inspire contemporary interpretations and debates on the nature of true spirituality. - Enduring Relevance in Devotional Verses:

Recited in various contexts within the Sikh tradition, Sidh Gosti not only reinforces doctrinal tenets but also serves as a vivid reminder that spiritual fulfillment is found in the perennial practice of Naam Simran. Its timeless dialogue invites modern devotees to question superficial religiosity and to seek a transformative, heartfelt engagement with the Divine.

Concluding Reflections

Guru Nanak’s Sidh Gosti: A Dialogue of Wisdom remains a seminal text in Sikh scripture—a masterful composition that engages with both the philosophical tenets and the practical demands of spiritual life. Through its conversational format, the text dismantles the allure of external mysticism and redirects the seeker to the inner light of divine love and remembrance. It eloquently encapsulates the fundamental assertion that liberation is not the reward of supernatural prowess but of sincere, devoted practice.